主管:中国科学院

主办:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所

出版:科学出版社

主办:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所

出版:科学出版社

人类学学报 ›› 2024, Vol. 43 ›› Issue (06): 1048-1063.doi: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2024.0090

收稿日期:2024-04-26

修回日期:2024-06-15

出版日期:2024-12-15

发布日期:2024-11-28

通讯作者:

张双权,研究员,主要研究方向为脊椎动物埋藏学与旧石器时代动物考古学。E-mail: zhangshuangquan@ivpp.ac.cn

作者简介:张乐,副教授,主要研究方向为旧石器时代动物考古学和埋藏学。E-mail: zhangyue2023@muc.edu.cn

基金资助:

ZHANG Yue1( ), ZHANG Shuangquan2,3(

), ZHANG Shuangquan2,3( )

)

Received:2024-04-26

Revised:2024-06-15

Online:2024-12-15

Published:2024-11-28

摘要:

本文从微观宏观结合、定量定性并重的研究视角,对穿洞遗址1981年出土的数件典型骨器的形态特征、加工技术和使用痕迹进行了系统分析,对其工艺和功能进行了较为详细的阐释与恢复。结果显示:穿洞古人类倾向于选择大型鹿类动物的长骨骨干制作尖刃器,而以牛的长骨骨干制作铲型器;加工骨器的技术包括打制、刮削、磨制、切刻、抛光等。此外,与早年研究结果有所不同,穿洞遗址中的两尖器应为复合工具,且其主要应用于钻孔或切割等活动而非通常所认知的渔猎;骨锥类工具可能用于兽皮穿孔;铲形器刃口形态各异,但其使用痕迹特征基本一致,表明其主要用于挖掘地下块茎类植物。本文为穿洞史前骨工业的技术特征、文化源流以及古人类生计模式、生存状态的探索与研究提供了新的证据。

中图分类号:

张乐, 张双权. 贵州普定穿洞遗址1981年出土的骨制品[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 1048-1063.

ZHANG Yue, ZHANG Shuangquan. Bone artifacts unearthed from the Chuandong cave site in Puding of Guizhou in 1981[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2024, 43(06): 1048-1063.

图1 穿洞遗址出土的典型骨器 1~2.尖刃器Pointed bone tools:从左到右依次为144、142号标本的背面、右侧面、腹面、左侧面Dorsal, right lateral, ventral and left lateral views (from left to right) of specimens No. 144 and 142;3.尖刃器Pointed bone tool:从左到右依次为143号标本的背面、近端断面与腹面Dorsal, proximal, and ventral views (from left to right) of specimen No. 143;4, 6, 7.铲型器Spatulas:从左到右依次为145、147与146号标本的背面、右侧面、腹面、左侧面Dorsal, right lateral, ventral and left lateral views (from left to right) of specimens No. 145, 147 and 146;5.铲型器Spatula:从左到右依次为141号标本的背面、右侧面、腹面Dorsal, right lateral and ventral views (from left to right) of specimen No. 141。比例尺Scales: 1cm.

Fig.1 The exemplary bone tools from the Chuandong cave

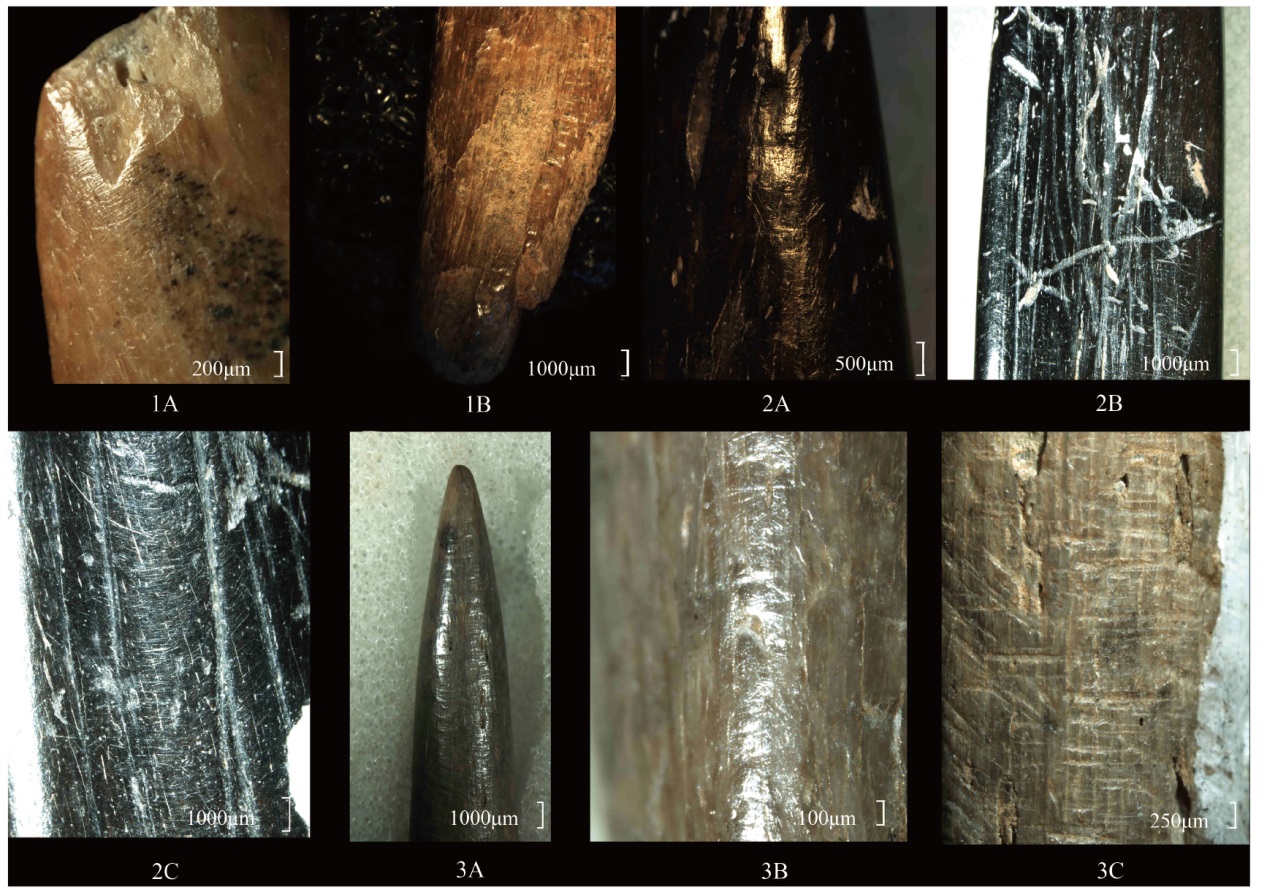

图2 尖刃器表面的制作痕迹与使用痕迹 1. 144号标本Specimen No. 144:A.上部尖表面密集分布着垂直于长轴的线状痕迹,其边缘被磨圆、磨光Groups of transverse striations on the distal end, with edges smoothed by heavy polish;B.下部尖腹面分布着成组的横向、较宽、短的平行线状痕迹,疑似绑缚造成的压痕Groups of transverse, wider and shorter striations on the proximal end, which were likely produced by the pressure exerted by a binding agent while in hafting。 2. 142号标本Specimen No.142:A.尖端分布着成组的较深、宽的横向线状痕迹,它们的边缘被更细小的线状痕迹磨圆磨光Groups of transverse, deep and wide striations on the pointed end, with edges covered by micro-striations;B.器身腹面分布着较宽的线状切刻痕迹Engraved lines on mesial part of the tool;C.器身光亮表面布满密集、极细的横向线状痕,可能是古人类有意识地抛光修理造成Intensive micro-striations on mesial part of the tool, suggesting that it was intentionally polished by the crafter。 3. 143号标本Specimen No. 143:A.尖端反光特性明显,磨制痕迹边缘被严重磨光磨圆The reflective tip of the tool, with grinding traces partially obliterated by polish;B.尖端表面分布一些比磨制痕迹细小很多的横向线状痕迹,边缘被磨圆磨光Groups of fine transverse striations developed on the pointed end, with their edges smoothed by a heavy polish. C.标本表面布满横向或斜向的磨制痕迹,它们分布于数个平行于器物长轴的窄平面上Oblique or transverse grinding marks on distinct adjacent facets parallel to the long axis.

Fig.2 Manufacturing traces and use-wear on the pointed tools

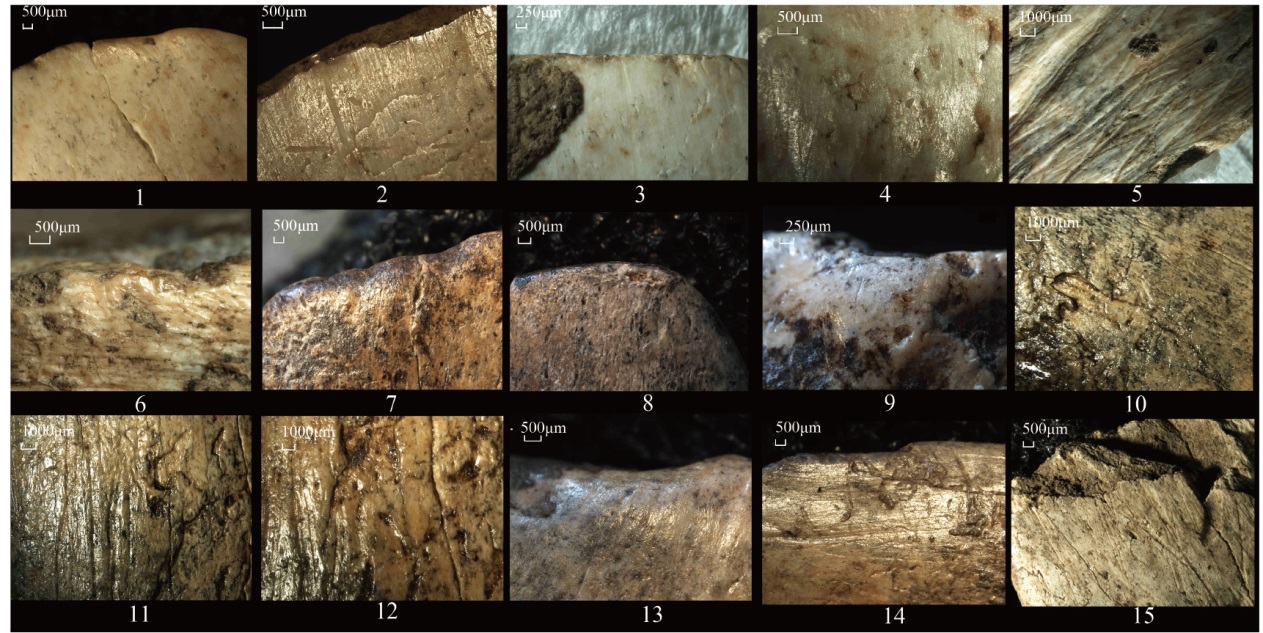

图3 铲形器的表面痕迹 1-6. 145号标本Specimen No.145:1, 2.上部刃缘背、腹面分布的线状痕迹Linear striations on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the distal end;3.上部刃缘中部垂直于器物长轴的细长小面The middle part of the distal end, with a flat crushed facet perpendicular to the long axis of the tool;4.下部刃缘表面分布的线状痕迹Linear striations on the proximal end;5.腹面的切刻痕迹Engraved lines on the ventral surface;6.两侧边缘腹面分布着连续、磨光磨圆的小疤Polished scars on the ventral part of the lateral sides。 7-12. 146号标本Specimen No.146:7.上部刃缘左侧部分被磨圆磨光,其上可见三处微凹陷The polished distal end, with three. depressions on its left part;8.上部刃缘右侧细长的、垂直于器身的平面刃The right part of the distal end, with a flat crushed facet perpendicular to the long axis of the tool;9.下部刃缘表面分布的细线状痕迹Linear striations on the proximal end;10.修整石制品造成的骨表脱落凹陷区Scaled areas created by the detachment of cortical flakes when the tool was used as a retoucher;11.背面的切刻痕迹Engraved lines on the dorsal surface;12.骨表脱落凹陷区内部分布的切刻痕Engraved lines observable in the scaled areas of the tools。 13-14. 147号标本Specimen No.147;13.上部刃缘表面分布的细线状痕迹Linear striations on the surfaces of the distal end14.器身背面的刮削痕迹Scraping marks on the dorsal surface of the tool. 15. 141号标本Specimen No.141:上部刃缘的细线状痕迹Linear striations on the distal end.

Fig.3 Manufacturing traces and use-wear on the Spatulas

| 上部Distal end | 中部 Mesial end | 下部刃 Proximal end | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 标本号Specimen number | 线状痕迹宽度Width of linear striations (μm) | 刃角 Angle | 腹面切刻痕迹宽度Width of engraved lines (μm) | 背面修理痕迹宽度Width of manufacturing traces (μm) | 两侧修疤Scars on lateral sides | 刃部修疤Scars on proximal end | 线状痕迹宽度Width of linear striations (μm) | 刃角Angle | ||

| 145 | 27~45 | 33° | 245~386 | 67-170 (scraping) | 是 Y | 是 Y | 31~48 | 76° | ||

| 147 | 38~45 | 40° | 346-470 | 133-224 (scraping) | 是 Y | 是 Y | NA | 30° | ||

| 146 | 31~57 | 45° | 287~471 | 344~672 (engraving) | 是 Y | 否 N | 30~46 | 57°~70° | ||

| 141 | 37~48 | 33° | NA | 13~19 (Polishing) | 是 Y | NA | NA | NA | ||

表1 铲形器的观察与测量表

Tab.1 Attributes of the spatulas

| 上部Distal end | 中部 Mesial end | 下部刃 Proximal end | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 标本号Specimen number | 线状痕迹宽度Width of linear striations (μm) | 刃角 Angle | 腹面切刻痕迹宽度Width of engraved lines (μm) | 背面修理痕迹宽度Width of manufacturing traces (μm) | 两侧修疤Scars on lateral sides | 刃部修疤Scars on proximal end | 线状痕迹宽度Width of linear striations (μm) | 刃角Angle | ||

| 145 | 27~45 | 33° | 245~386 | 67-170 (scraping) | 是 Y | 是 Y | 31~48 | 76° | ||

| 147 | 38~45 | 40° | 346-470 | 133-224 (scraping) | 是 Y | 是 Y | NA | 30° | ||

| 146 | 31~57 | 45° | 287~471 | 344~672 (engraving) | 是 Y | 否 N | 30~46 | 57°~70° | ||

| 141 | 37~48 | 33° | NA | 13~19 (Polishing) | 是 Y | NA | NA | NA | ||

| [1] | Klein RG. The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins[M]. the 3rd edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009 |

| [2] | Mellars P. The character of the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic transition in south-west France[A]. In: The Explanation of Culture Change:Models in Prehistory[C]. London: Duckworth, 1973, 255-276 |

| [3] | 吴秀杰, 张乐, 张双权. 四川资阳人遗址出土的骨锥[J]. 人类学学报, 2023, 42(1): 1-14 |

| [4] | 安家瑗. 华北地区旧石器时代的骨、角器[J]. 人类学学报, 2001, 20: 319-330 |

| [5] | McBrearty S, Brooks AS. The revolution that wasn’t: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2000, 39(5): 453-563 |

| [6] |

Henshilwood CS, d’Errico F, Marean CW, et al. An early bone tool industry from the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa: implications for the origins of modern human behaviour, symbolism and language[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2001, 41(6): 631-678

pmid: 11782112 |

| [7] | d’Errico F, Henshilwood C, Lawson G, et al. Archaeological evidence for the emergence of language, symbolism, and music-an alternative multidisciplinary perspective[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 2003, 17(1): 1-70 |

| [8] | Pei WC. The Upper Cave industry of Choukoutien[J]. Palaeontologia Sinica (Series D), 1939, 9: 1-58 |

| [9] | 黄慰文, 张镇洪, 傅仁义, 等. 海城小孤山的骨制品[J]. 人类学学报, 1986, 5: 259-266 |

| [10] | 蔡回阳. 白岩脚洞的人化石和骨制品[A]. 见: 董为(主编). 第十三届中国古脊椎动物学学术年会论文集[C]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 2012, 203-210 |

| [11] | Zhang S, d’Errico F, Backwell LR, et al. Ma’anshan cave and the origin of bone tool technology in China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2016, 65: 57-69 |

| [12] | 张森水. 穿洞史前遗址(1981年发掘)初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 1995, 14(2): 132-146 |

| [13] | 毛永琴, 曹泽田. 贵州穿洞遗址1979年发现的磨制骨器的初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2012, 31(4): 335-343 |

| [14] | Zhang S, Doyon L, Zhang Y, et al. Innovation in bone technology and artefact types in the late Upper Palaeolithic of China: Insights from Shuidonggou Locality 12[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2018, 93: 82-93 |

| [15] | Zhang Y, Gao X, Pei SW, et al. The bone needles from Shuidonggou locality 12 and implications for human subsistence behaviors in North China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 400: 149-157 |

| [16] |

d’Errico F, Doyon L, Zhang S, et al. The origin and evolution of sewing technologies in Eurasia and North America[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018, 125: 71-86

doi: S0047-2484(18)30085-X pmid: 30502899 |

| [17] | 俞锦林. 贵州普定县穿洞古人类化石及其文化遗物的初步研究[J]. 南京大学学报(自然), 1984, 145 |

| [18] | Wang Y, Zhang X, Sun X, et al. A new chronological framework for Chuandong Cave and its implications for the appearance of modern humans in southern China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2023, 178: 103344 |

| [19] | Zhao M, Shen GJ, He JN, et al. AMS 14C dating of the hominin archaeological site Chuandong Cave in Guizhou Province, southwestern China[J]. Quaternary International, 2017, 447: 102-110 |

| [20] | Shipman P, Rose J. Early hominid hunting, butchering, and carcass-processing behaviors: Approaches to the fossil record[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 1983, 2(1): 57-98 |

| [21] | Behrensmeyer AK, Gordon KD, Yanagi GT. Trampling as a cause of bone surface damage and pseudo-cutmarks[J]. Nature, 1986, 319(6056): 768-771 |

| [22] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 1-552 |

| [23] | Fisher JW. Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 1995, 2(1): 7-68 |

| [24] | White T. Prehistoric Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346[M]. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992 |

| [25] | Dominguez-Rodrigo M, de Juana S, Galan AB, et al. A new protocol to differentiate trampling marks from butchery cut marks[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009, 36(12): 2643-2654 |

| [26] | Bradfield J. Macrofractures on bone-tipped arrows: analysis of hunter-gatherer arrows in the Fourie collection from Namibia[J]. Antiquity, 2012, 86(334): 1179-1191 |

| [27] | Bradfield J, Brand T. Results of utilitarian and accidental breakage experiments on bone points[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2013, 1-12 |

| [28] | Bradfield J, Lombard M. A macrofracture study of bone points used in experimental hunting with reference to the South African Middle Stone Age[J]. South African Archaeological Bulletin, 2011, 66: 67-76 |

| [29] | Buc N. Experimental series and use-wear in bone tools[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(3): 546-557 |

| [30] | Byrd BF, Monahan CM. Death, Mortuary Ritual, and Natufian Social Structure[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 1995, 14(3): 251-287 |

| [31] |

d’Errico F, Henshilwood CS. Additional evidence for bone technology in the southern African middle stone age[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2007, 52(2): 142-163

pmid: 16996574 |

| [32] | d’Errico F. The invisible frontier. A multiple species model for the origin of behavioral modernity[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2003, 12(4): 188-202 |

| [33] | Griffitts JL. Bone tools and technological choice: Change and stability on the Northern Plains[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. Arizona: University of Arizona, 2006 |

| [34] | Legrand A, Radi G. Manufacture and use of bone points from Early Neolithic Colle Santo Stefano, Abruzzo, Italy[J]. Journal of Field Archaeology, 2008, 33(3): 305-320 |

| [35] | Legrand A, Sidéra I. Methods, means and results when studying European bone industries[A]. In: Gates St-Pierre C, Walker R(eds). Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies[C]. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1622[C]. 2007, 291-304 |

| [36] | LeMoine GM. Use wear on bone and antler tools from the Mackenzie Delta, Northwest Territories[J]. American Antiquity, 1994, 59(2): 316-334 |

| [37] | Gates Saint-Pierre C, Walker RB. Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies[C]. British Archaeological Reports International Series 1622. Oxford:Archaeopress, 2007, 1-182 |

| [38] | Karavanić I, Šokec T. The Middle Paleolithic percussion or pressure flaking tools? The comparison of experimental and archaeological material from Croatia[J]. Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu, 2003, 20(1): 5-14 |

| [39] | Backwell LR, d’Errico F. The first use of bone tools: a reappraisal of the evidence from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania[J]. Palaeontologia africana, 2004, 40(9): 95-158 |

| [40] | Blasco R, Rosell J, Cuartero F, et al. Using bones to shape stones: MIS 9 bone retouchers at both edges of the Mediterranean Sea[J]. Plos One, 2013, 8(10): e76780 |

| [41] | Daujeard C, Moncel MH, Fiore I, et al. Middle Paleolithic bone retouchers in Southeastern France: Variability and functionality[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 326: 492-518 |

| [42] | Moigne AM, Valensi P, Auguste P, et al. Bone retouchers from Lower Palaeolithic sites: Terra Amata, Orgnac 3, Cagny-l’Epinette and Cueva del Angel[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 409: 195-212 |

| [43] | Tejero JM, Arrizabalaga Á, Villaluenga A. The Proto-Aurignacian and Early Aurignacian retouchers of Labeko Koba (Basque Country, Spain). A techno-economic and chrono-cultural interpretation using lithic and faunal data[J]. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2016, 15(8): 994-1010 |

| [44] | Yeshurun R, Tejero JM, Barzilai O, et al. Upper Palaeolithic bone retouchers from Manot Cave (Israel): A preliminary analysis of a (yet) rare phenomenon in the Levant[J]. The Origins of Bone Tool Technologies, 2017, 1-9 |

| [45] | Buc N, Loponte D. Bone Tool Types and Microwear Patterns: Some Examples from the Pampa Region, South America[C]. In: Gates St-Pierre C, Walker R(eds). Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies[M]. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports International Series 1622, Archaeopress, 2007, 143-157 |

| [46] | d’Errico F. La vie sociale de l’art mobilier Paléolithique. Manipulation, transport, suspension des objets on os, bois de cervidés, ivoire[J]. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 1993, 12(2): 145-174 |

| [47] | d’Errico F, Backwell LR, Berger LR. Bone tool use in termite foraging by early hominids and its impact on our understanding of early hominid behaviour: research in action[J]. South African Journal of Science, 2001, 97(3): 71-75 |

| [48] | d’Errico F, Backwell L. Assessing the function of early hominin bone tools[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009, 36(8): 1764-1773 |

| [49] | Pasveer J. Bone Artefacts from Liang Lemdubuand Liang Nabulei Lisa, Aru Islands[J]. Terra Australis, 2007, 22: 235-254 |

| [50] | Sillitoe P. Made in Niugini: technology in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea[M]. London: British Museum Publications, 1988 |

| [51] | Pasveer JM, Bellwood P. Prehistoric bone artefacts from the northern Moluccas, Indonesia[A]. In: Keates SG, Pasveer JM(eds). Quaternary Research in Indonesia[C]. Lisse: AA. Balkema Publishers, 2004, 301-359 |

| [52] | Pasveer JM. The Djief Hunters, 26,000 Years of Rainforest Exploitation on the Bird’s Head of Papua, Indonesia[C]. Modern Quaternary Research in Southeast Asia. Lisse: AA. Balkema, 2004, 17 |

| [53] | Backwell L, d’Errico F, Wadley L. Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort Layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(6): 1566-1580 |

| [54] | Brain CK, Shipman P. The Swartkrans bone tools[A]. In: In: Brain CK(ed). Swartkrans: a Cave’s Chronicle of Early Man: Transvaal Museum Monograph, 1993, 195-215 |

| [55] | 刘旻, 王运辅, 付永旭, 等. 简论贵州高原史前时代的骨角铲、锥系统[J]. 南方文物, 2019, 5: 210-219 |

| [1] | 关莹, 王社江, 周振宇, 高星, 张茜. 洛南手斧上的淀粉粒与古人类使用石器的策略[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 1064-1074. |

| [2] | 张晓凌, 王呈祥, 谭韵瑶, 靳英帅, 杨紫衣, 王社江. 青藏高原旧石器时代考古发现与研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 967-978. |

| [3] | 李浩, 肖培源, 彭培洺, 王雨晴, 陈清懿, Ikram QAYUM, 贾真秀, 阮齐军, 陈发虎. 西南丝绸之路上的旧石器文化与人群交流[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(06): 979-992. |

| [4] | Evgeny P RYBIN, Arina M KHATSENOVICH. 旧石器时代晚期初段色楞格河人类的扩散路线[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(05): 780-796. |

| [5] | 高黄文, 刘颖杰, 陆成秋, 孙雪峰, 黄旭初, 徐静玥. 湖北郧阳包包岭遗址2021年发掘简报[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(05): 828-838. |

| [6] | 韩芳, 李冀源, 乔虹, 徐海伦, 何虹霖, 高璇, 吕红亮, 杜战伟, 蔡林海, 甄强, 马文灵. 环青海湖地区细石叶遗存新发现[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(05): 839-852. |

| [7] | 成楠, 夏文婷, 杨青, 吉学平, 字兴, 范斌, 邹梓宁, 余童, 张俞, 石林, 张吾奇, 郑洪波. 云南巍山三鹤洞地点的石制品及年代与环境[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(03): 392-404. |

| [8] | 肖培源, 阮齐军, 高玉, 贾真秀, 张明, 杨李靖, 刘建辉, 李三灵, 李浩. 2022年云南宾川盆地旧石器遗址调查报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(03): 448-457. |

| [9] | Hiroyuki SATO, Kazuki MORISAKI. 日本旧石器晚期石器技术起源的新考古学与人类学证据[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(03): 470-487. |

| [10] | 王华, 李占扬, Thijs van KOLFSCHOTEN. 德国西宁根与中国灵井的骨器比较[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(02): 214-232. |

| [11] | 赵清坡, 马欢欢. 河南灵宝旧石器考古调查报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(02): 321-330. |

| [12] | 许竞文, 浣发祥, 杨石霞. 旧石器时代考古中出土的赭石及相关遗物的研究方法[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(02): 331-343. |

| [13] | 高星, 张月书, 李锋, 陈福友, 王晓敏, 仪明洁. 泥河湾盆地东谷坨遗址2016-2019年发掘简报[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(01): 106-121. |

| [14] | 赵云啸, 仝广, 涂华, 赵海龙. 河北省泥河湾盆地石沟遗址C区发掘简报[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(01): 122-131. |

| [15] | 周士航, 何湘栋, 徐静玥, 李潇丽, 牛东伟. 蔚县盆地东沟遗址2017年度发掘简报[J]. 人类学学报, 2024, 43(01): 132-142. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

全文 239

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

摘要 269

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

京ICP证05002819号-3

京ICP证05002819号-3