主管:中国科学院

主办:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所

出版:科学出版社

主办:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所

出版:科学出版社

人类学学报 ›› 2020, Vol. 39 ›› Issue (04): 532-554.doi: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2020.0061cstr: 32091.14.j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2020.0061

张颖奇1,2,3( ), Terry HARRISON4, 吉学平5,6

), Terry HARRISON4, 吉学平5,6

收稿日期:2020-06-03

修回日期:2020-09-10

出版日期:2020-11-15

发布日期:2020-11-23

作者简介:张颖奇,博士,研究员,主要从事古灵长类哺乳动物学研究。E-mail:基金资助:

ZHANG Yingqi1,2,3( ), Terry HARRISON4, JI Xueping5,6

), Terry HARRISON4, JI Xueping5,6

Received:2020-06-03

Revised:2020-09-10

Online:2020-11-15

Published:2020-11-23

摘要:

长久以来,指骨弯曲程度都被用来推断化石灵长类移动行为方式。此前已有一些方法被提出并用于定量化比较指骨弯曲程度,包括半径弯曲程度法(radius of curvature)、夹角法(included angle, IA)、标准化矩臂弯曲程度法(normalized curvature moment arm, NCMA)以及高精度多项式曲线拟合法(high-resolution polynomial curve fitting, HR-PCF)。然而,在对指骨弯曲程度进行定量化的过程中,这些方法都显示出了理论或技术上的局限性。因此,在运用这些方法之前,应当谨慎考虑其适用性和精确程度对分析结果所产生的影响。鉴于此,为了避免先前方法中存在的问题并更加精确地定量描述指骨弯曲程度,本文介绍了一种新方法作为替代。该方法基于对指骨侧视图背侧轮廓曲线几何形态测量学标志点数据的四阶多项式曲线拟合,称为几何形态测量学—多项式曲线拟合法(4th order polynomial curve fitting on geometric morphometric landmark data, GM-PCF)。它以标准化指骨曲线高度(normalized phalangeal curve height, NPCH)作为指骨弯曲程度的定量指标,并且可以将平均标准化指骨曲线进行可视化以用于其弯曲程度的直观对比。此外,它还可以提供在解释指骨弯曲程度的功能意义中非常关键的指骨(背侧轮廓曲线)长度比例信息。GM-PCF还能够分析化石中常见的不完整的指骨。为了检验新方法的适用性,我们从现生类人猿(anthropoids)中选取了15个涵盖灵长类大部分移动行为方式的类群作为参考样本,采用GM-PCF方法对其指骨弯曲程度进行了定量分析,结果表明标准化指骨曲线高度(NPCH)对灵长类移动行为方式有很好的指示意义,配合指骨曲线长度,还可以更进一步了解树栖四足行走(arboreal quadrupedalism)、悬垂(suspension)与摆荡(brachiation)等行为与灵长类体型大小的关系。作为个案,我们采用新方法对中国中新世的两种禄丰古猿(禄丰禄丰古猿Lufengpithecus lufengensis和蝴蝶禄丰古猿Lufengpithecus hudienensis)的指骨弯曲程度与参考样本进行了对比,并根据对比结果对其最为可能的移动行为方式偏好进行了推断。

中图分类号:

张颖奇, Terry HARRISON, 吉学平. 利用指骨弯曲程度推断化石人猿超科成员移动行为方式的新方法:以禄丰古猿为例[J]. 人类学学报, 2020, 39(04): 532-554.

ZHANG Yingqi, Terry HARRISON, JI Xueping. Inferring the locomotor behavior of fossil hominoids from phalangeal curvature using a novel method: Lufengpithecus as a case study[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2020, 39(04): 532-554.

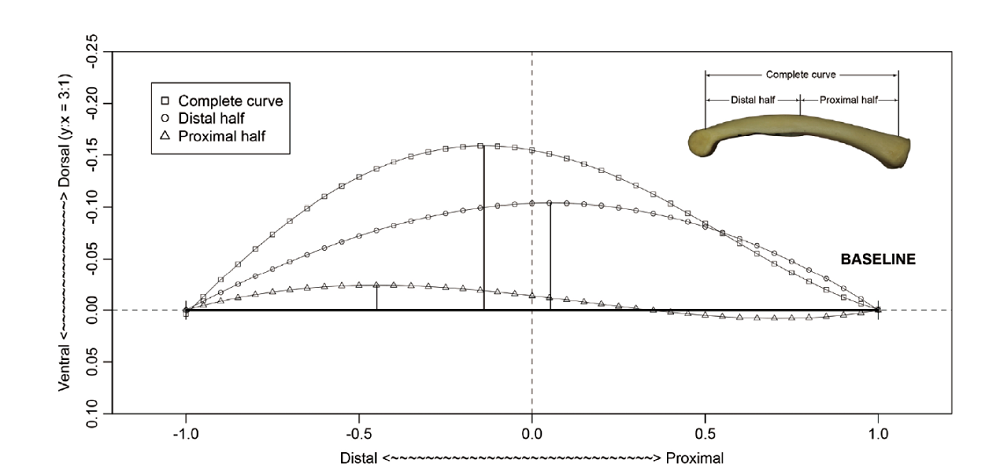

Fig.1 The complete curve, distal half, and proximal half of the average normalized phalangeal curve of 56 manual 3rd proximal phalanges of hylobatids, showing the asymmetry of phalangeal curvature Vertical black lines represent the normalized phalangeal curve height (NPCH) for the corresponding average curve. Aspect ratio of y/x is exaggerated to 3:1 to display the curvature more clearly

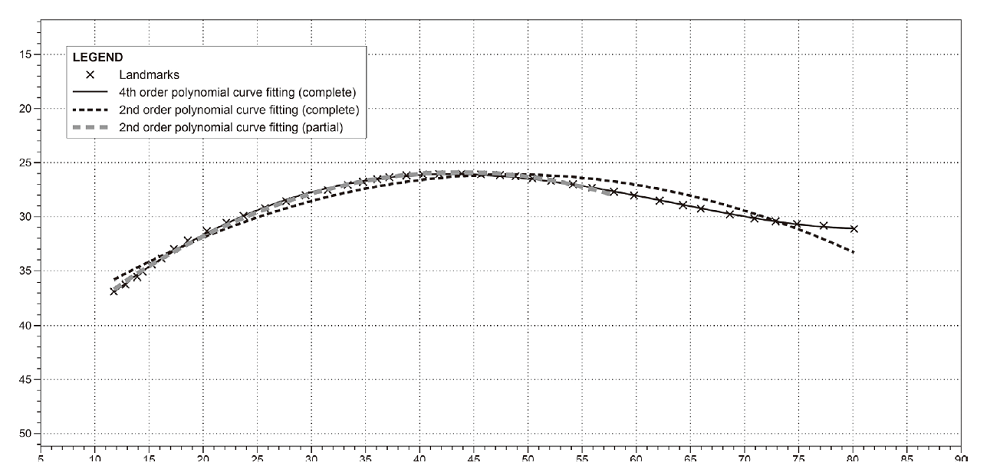

Fig.2 Comparison between 4th order and 2nd order polynomial curve fitting on the landmark set collected from a manual 3rd proximal phalanx of Pongo pygmaeus (AMNH 28252, same specimen as in Figure 3 and Figure 4, scenario 1), showing the advantage of 4th order polynomial curve fitting over 2nd order polynomial curve fitting when depicting complete phalangeal curves. [unit: mm]

Fig.3 Method of collecting landmarks used in the 4th order polynomial curve fitting to depict phalangeal curvature, demonstrated on the horizontally flipped photo of a manual 3rd proximal phalanx of Pongo pygmaeus (AMNH 28252) START POINT: where the proximal tangential line of the phalangeal head (trochlea) perpendicular to the shaft meets with the dorsal outline of the phalanx in side view. END POINT: where the metaphysis starts on the dorsal surface of phalanx in side view

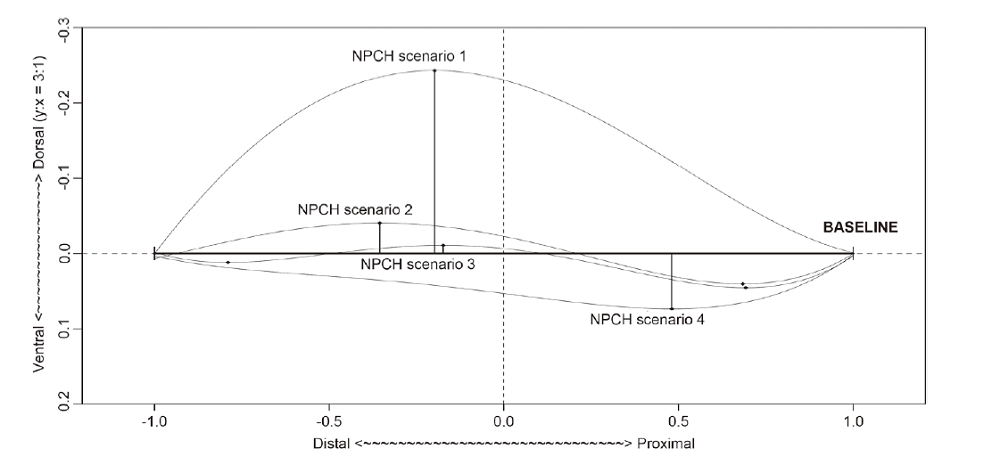

Fig.4 All four possible scenarios for calculation of normalized phalangeal curve height (NPCH) Scenario 1: when there is only one inflection point (“ω” on the normalized phalangeal curve, the same below) above the baseline, the distance between this inflection point and the baseline is defined as NPCH, which occurs in most phalanges (example specimen: the manual 3rd proximal phalanx of Pongo pygmaeus, AMNH 28252). Scenario 2: when there are two inflection points on the curve, the distance between the distally located and dorsally convex inflection point and the baseline is defined as NPCH, which occurs in most intermediate phalanges and is the second most common scenario (example specimen: the manual 3rd intermediate phalanx of Pongo pygmaeus, AMNH 28253). Scenario 3: when there are three inflection points on the curve, the distance between the intermediate and dorsally convex inflection point and the baseline is defined as NPCH, which only occurs in some pollical or hallucal proximal phalanges (example specimen: the pollical proximal phalanx of Pongo pygmaeus, NMNH 153824). Scenario 4: when there is only one inflection point below the baseline, the distance between this inflection point and the baseline is defined as NPCH, which occurs in some pollical and hallucal proximal phalanges, and pedal intermediate phalanges of Gorilla, Pan, and Homo (example specimen: the pollical proximal phalanx of Pongo abelii, NMNH 143586). Aspect ratio of y/x is exaggerated to 3:1 to display the curvature more clearly

| individual | manual phalanges | pedal phalanges | locomotion* | arboreality vs. terrestriality* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pollical proximal | ray II-V proximal | ray II-V intermediate | hallucal proximal | ray II-V proximal | ray II-V intermediate | |||||

| Hylobatidae | 56 | 53 | 222 | 213 | 49 | 192 | 170 | suspension, brachiation, climbing | arboreal | |

| Pongo spp. | 41 | 41 | 162 | 162 | 38 | 157 | 158 | suspension, climbing | arboreal | |

| Gorilla spp. | 36 | 28 | 122 | 118 | 28 | 115 | 103 | knuckle-walking | terrestriality > arboreality | |

| Pan spp. | 45 | 40 | 160 | 156 | 41 | 170 | 157 | knuckle-walking, suspension, climbing | terrestriality ≈ arboreality | |

| Homo sapiens | 67 | 67 | 268 | 268 | 67 | 267 | 223 | bipedalism | terrestrial | |

| Papio spp. | 6 | 6 | 24 | 24 | 6 | 24 | 19 | quadrupedalism | terrestrial | |

| Macaca mulatta | 35 | 35 | 140 | 140 | 35 | 140 | 140 | quadrupedalism, climbing | terrestriality > arboreality | |

| Trachypithecus spp. | 8 | 5 | 28 | 20 | 8 | 32 | 24 | quadrupedalism, climbing, leaping | arboreal | |

| Semnopithecus spp. | 3 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 5 | quadrupedalism, climbing, leaping | arboreal or semi-terrestrial | |

| Presbytis spp. | 5 | 4 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 18 | 12 | leaping, quadrupedalism | arboreal | |

| Rhinopithecus roxellana | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | quadrupedalism, climbing, brachiation | arboreal | |

| Colobus angolensis | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | quadrupedalism, leaping, climbing | arboreal | |

| Ateles spp. | 10 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 8 | 32 | 32 | quadrupedalism, climbing, suspension | arboreal | |

| Alouatta spp. | 2 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 6 | quadrupedalism, climbing | arboreal | |

| Cebus spp. | 12 | 12 | 48 | 48 | 7 | 48 | 40 | quadrupedalism, climbing | arboreal | |

| Total (5703) | 328 | 295 | 1257 | 1216 | 296 | 1218 | 1093 | |||

Tab.1 Sample size of phalangeal specimens of extant anthropoid primates included in the present study and their locomotor behavior modes

| individual | manual phalanges | pedal phalanges | locomotion* | arboreality vs. terrestriality* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pollical proximal | ray II-V proximal | ray II-V intermediate | hallucal proximal | ray II-V proximal | ray II-V intermediate | |||||

| Hylobatidae | 56 | 53 | 222 | 213 | 49 | 192 | 170 | suspension, brachiation, climbing | arboreal | |

| Pongo spp. | 41 | 41 | 162 | 162 | 38 | 157 | 158 | suspension, climbing | arboreal | |

| Gorilla spp. | 36 | 28 | 122 | 118 | 28 | 115 | 103 | knuckle-walking | terrestriality > arboreality | |

| Pan spp. | 45 | 40 | 160 | 156 | 41 | 170 | 157 | knuckle-walking, suspension, climbing | terrestriality ≈ arboreality | |

| Homo sapiens | 67 | 67 | 268 | 268 | 67 | 267 | 223 | bipedalism | terrestrial | |

| Papio spp. | 6 | 6 | 24 | 24 | 6 | 24 | 19 | quadrupedalism | terrestrial | |

| Macaca mulatta | 35 | 35 | 140 | 140 | 35 | 140 | 140 | quadrupedalism, climbing | terrestriality > arboreality | |

| Trachypithecus spp. | 8 | 5 | 28 | 20 | 8 | 32 | 24 | quadrupedalism, climbing, leaping | arboreal | |

| Semnopithecus spp. | 3 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 5 | quadrupedalism, climbing, leaping | arboreal or semi-terrestrial | |

| Presbytis spp. | 5 | 4 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 18 | 12 | leaping, quadrupedalism | arboreal | |

| Rhinopithecus roxellana | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | quadrupedalism, climbing, brachiation | arboreal | |

| Colobus angolensis | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | quadrupedalism, leaping, climbing | arboreal | |

| Ateles spp. | 10 | 0 | 40 | 40 | 8 | 32 | 32 | quadrupedalism, climbing, suspension | arboreal | |

| Alouatta spp. | 2 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 6 | quadrupedalism, climbing | arboreal | |

| Cebus spp. | 12 | 12 | 48 | 48 | 7 | 48 | 40 | quadrupedalism, climbing | arboreal | |

| Total (5703) | 328 | 295 | 1257 | 1216 | 296 | 1218 | 1093 | |||

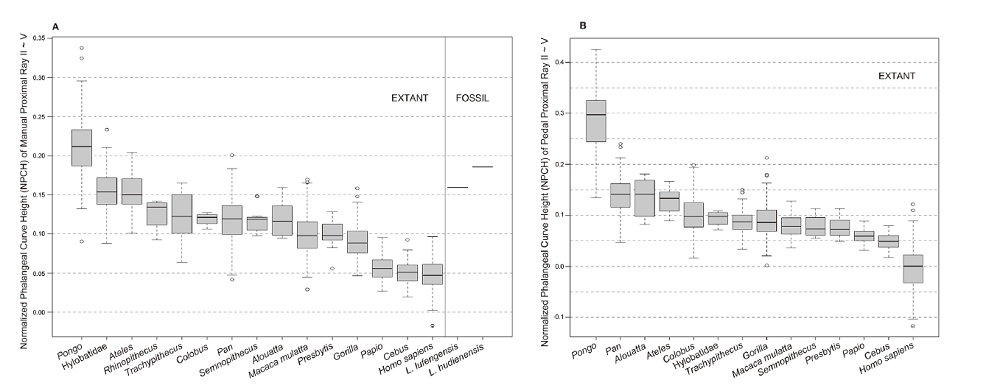

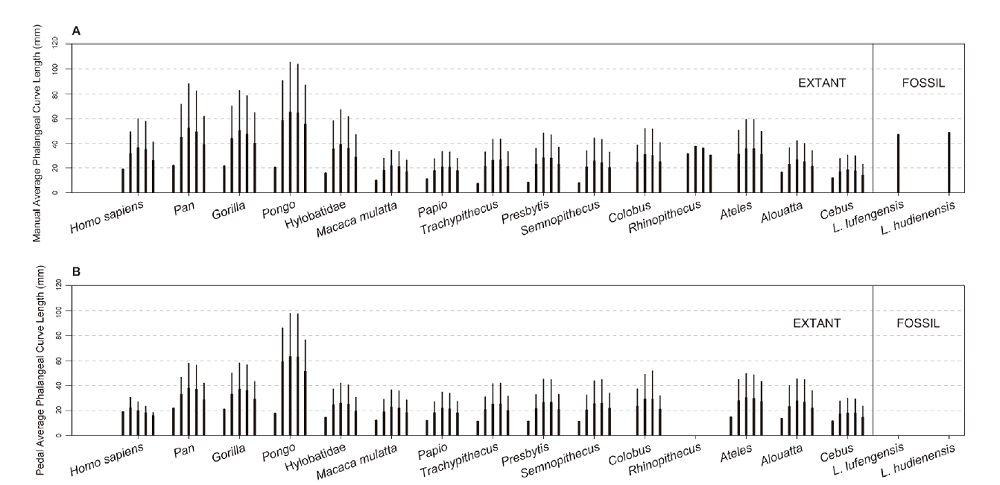

Fig.5 NPCHs of ray II-V proximal phalanges of extant anthropoids (plotted in decreasing order of NPCH) and Lufengpithecus A) Boxplot of NPCHs of manual proximal phalanges. B) Boxplot of NPCHs of pedal proximal phalanges. Sample sizes can be found in Figures 7-9

Fig.6 Phalangeal proportions (proximal and intermediate) of Lufengpithecus and extant anthropoids A) Manual phalangeal proportions (proximal and intermediate). B) Pedal phalangeal proportions (proximal and intermediate). The thicker vertical lines represent average curve length of proximal phalanges, while thinner vertical lines represent average curve length of intermediate phalanges. For extant anthropoids, all five rays are plotted in order (ray I to ray V, from left to right). When there are no data for ray, it is left blank. For Lufengpithecus, ray II-V phalanges are combined. Sample sizes can be found in Figures 7-9

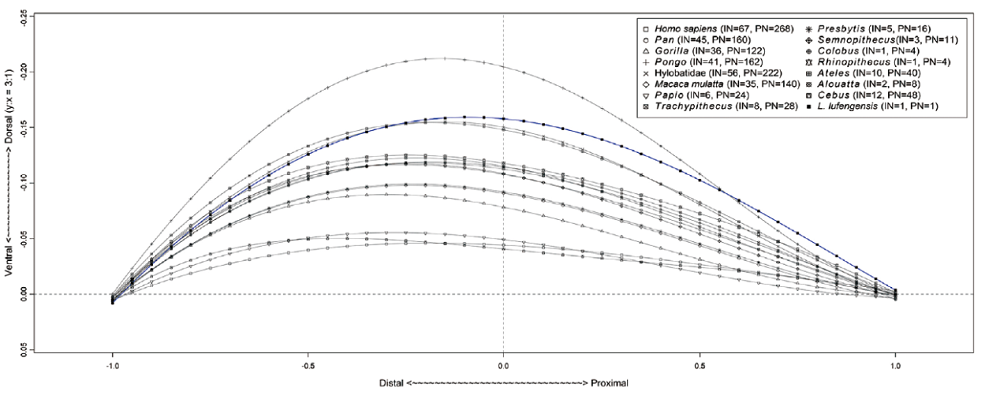

Fig.7 Average normalized phalangeal curve of the manual ray II-V proximal phalanx of Lufengpithecus lufengensis (PA 1057) compared with those of extant anthropoids IN = individual number; PN=phalanx number. L. lufengensis is highlighted by the thicker line. Aspect ratio of y/x is exaggerated to 3:1 to display the curvature more clearly

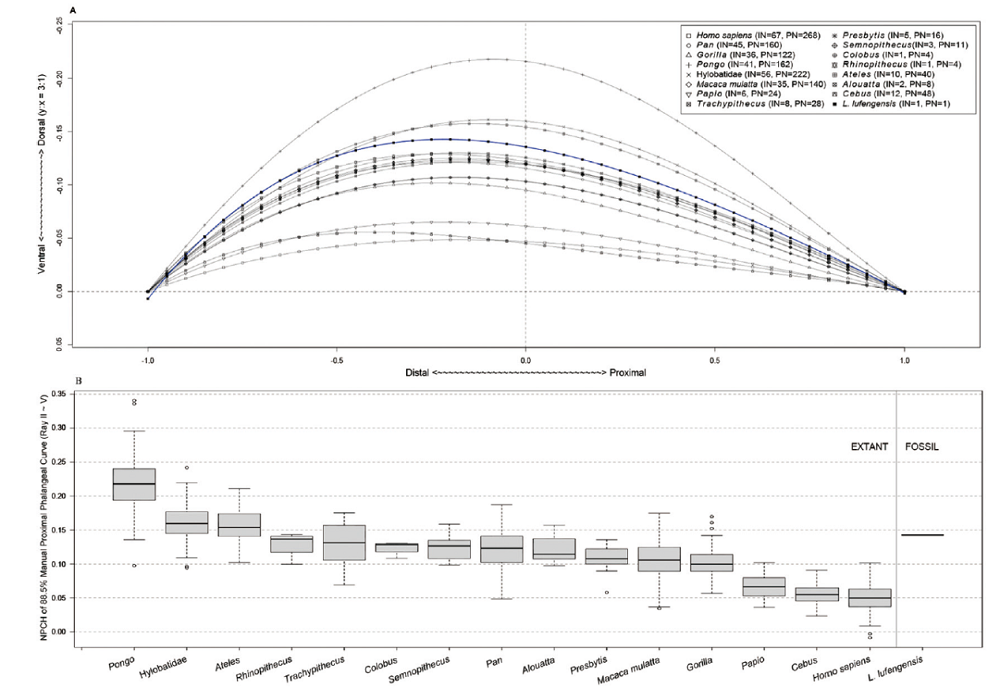

Fig.8 Average normalized phalangeal curve and NPCH of the incomplete manual ray II-V proximal phalanx (PA 1056) of Lufengpithecus lufengensis compared with those of extant anthropoids A) Normalized phalangeal curve of PA 1056 compared with 88.5% average normalized phalangeal curves of manual lateral phalanges of extant anthropoids. Aspect ratio of y/x is exaggerated to 3:1 to display the curvature more clearly. B) Boxplot of NPCH of PA 1056 (right) and those of 88.5% average normalized phalangeal curves of manual lateral phalanges of extant anthropoids (left). Extant anthropoids are plotted in decreasing order of NPCH

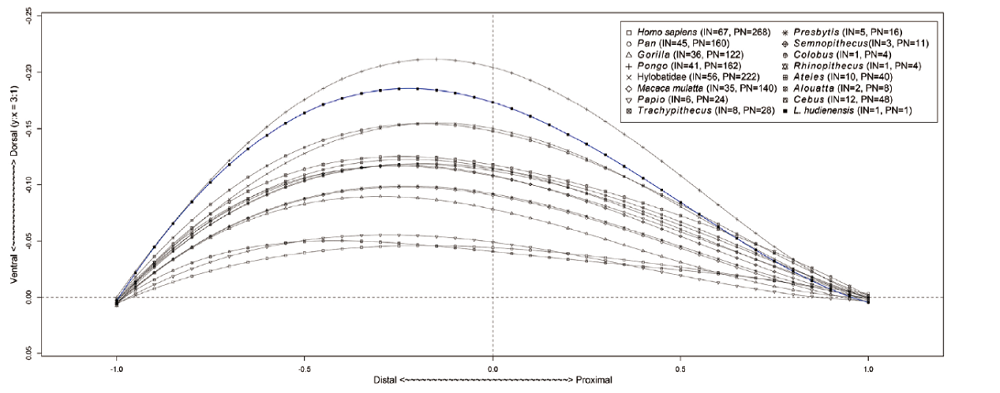

Fig.9 Average normalized phalangeal curve of the manual ray II-V proximal phalanx of Lufengpithecus hudienensis (YV 6103) compared with those of extant anthropoids IN=individual number; PN=phalanx number. L. hudienensis is highlighted by the thicker line. Aspect ratio of y/x is exaggerated to 3:1 to display the curvature more clearly

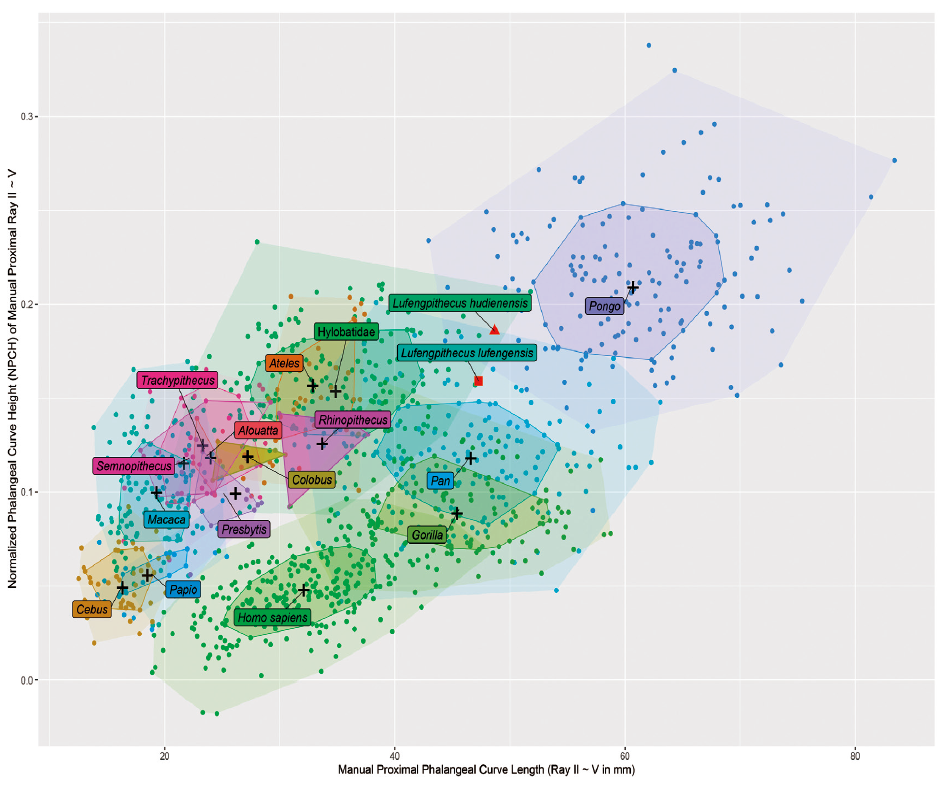

Fig.10 Bagplot of manual proximal phalangeal curve length of ray II-V against NPCH of manual proximal ray II-V For each group, + represents the Tukey median; the inner polygon is the bag that contains 50% of the data points; the outer polygon is the fence that separates inliers from outliers

| [1] | Lewis OJ. Functional morphology of the evolving hand and foot [M]. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989, 1-359 |

| [2] | Preuschoft H, Chivers DJ. Hands of primates[M]. New York: Springer, 1993, 1-421 |

| [3] | Kivell TL, Lemelin P, Richmond BG, Schmitt D. The evolution of the primate hand: Anatomical, developmental, functional, and paleontological evidence[M]. New York: Springer, 2016, 1-589 |

| [4] | Erikson GE. Brachiation in New World monkeys and in anthropoid apes[J]. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, 1963,10, 135-164 |

| [5] | Oxnard CE. Locomotor adaptations in the primate forelimb[J]. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, 1963,10, 165-182 |

| [6] | Tuttle RH. Knuckle-walking and the evolution of hominoid hands[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1967,26, 171-206 |

| [7] |

Tuttle RH. Knuckle-walking and the problem of human origins[J]. Science, 1969,166, 953-961

URL pmid: 5388380 |

| [8] | Tuttle RH. Evolution of hominid bipedalism and prehensile capabilities[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 1981,292, 89-94 |

| [9] |

Susman RL. Comparative and functional morphology of hominoid fingers[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1979,50, 215-236

URL pmid: 443358 |

| [10] |

Susman RL. Hand of Paranthropus robustus from Member 1, Swartkrans: fossil evidence for tool behavior[J]. Science, 1988,240, 781-784

doi: 10.1126/science.3129783 URL pmid: 3129783 |

| [11] |

Susman RL. Oreopithecus bambolii: an unlikely case of hominidlike grip capability in a Miocene ape[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2004,46, 105-117

URL pmid: 14698686 |

| [12] |

Stern JT, Susman RL. The locomotor anatomy of Australopithecus afarensis[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1983,60, 279-317

URL pmid: 6405621 |

| [13] | Susman RL, Stern JT, Jungers WL. Arboreality and bipedality in the Hadar hominids[J]. Folia Primatologica, 1984,43, 113-156 |

| [14] | Rose MD. Further hominoid postcranial specimens from the Late Miocene Nagri Formation of Pakistan[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1986,15, 333-367 |

| [15] | Zhang Y, Peng Y, Ye Z. Study on the functional morphology of some bones of Rhinopithecus[J]. Zoological Research, 1985,6, 175-183 |

| [16] | Harrison T. A reassessment of the phylogenetic relationships of Oreopithecus bambolii Gervais[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1986,15, 541-583 |

| [17] | Harrison T. The implications of Oreopithecus bambolii for the origins of bipedalism [A]. In: Coppens Y, Senut B eds. Origine(s) de la bipédie chez les hominidés. Paris: CNRS, 1991, pp. 235-244 |

| [18] | Sarmiento EE. The phylogenetic position of Oreopithecus and its significance in the origin of the Hominoidea[J]. American Museum Novitates, 1987,2881, 1-44 |

| [19] | Begun DR. Catarrhine phalanges from the Late Miocene (Vallesian) of Rudabánya, Hungary[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1988,17, 413-438 |

| [20] | Begun DR. New catarrhine phalanges from Rudabánya (Northeastern Hungary) and the problem of parallelism and convergence in hominoid postcranial morphology[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1993,24, 373-402 |

| [21] | Godinot M, Beard KC. Fossil primate hands: a review and an evolutionary inquiry emphasizing early forms[J]. Human Evolution, 1992,6, 307-354 |

| [22] | Godinot M, Beard KC. A survey of fossil primate hands [A], In: Preuschoft H, Chivers DJ eds. Hands of Primates. New York: Springer, 1993, 335-378 |

| [23] | Hamrick MW, Meldrum DJ, Simons EL. Anthropoid phalanges from the Oligocene of Egypt[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1995,28, 121-145 |

| [24] |

Stern JT, Jungers WL, Susman RL. Quantifying phalangeal curvature: an empirical comparison of alternative methods[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1995,97, 1-10

URL pmid: 7645670 |

| [25] |

Jungers WL, Godfrey LR, Simons EL, Chatrath PS. Phalangeal curvature and positional behavior in extinct sloth lemurs (Primates, Palaeopropithecidae)[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1997,94, 11998-12001

doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11998 URL pmid: 11038588 |

| [26] |

Nakatsukasa M, Kunimatsu Y, Nakano Y, Takano T, Ishida H. Comparative and functional anatomy of phalanges in Nacholapithecus kerioi, a Middle Miocene hominoid from northern Kenya[J]. Primates, 2003,44, 371-412

doi: 10.1007/s10329-003-0051-y URL pmid: 14508653 |

| [27] |

Deane AS, Kremer EP, Begun DR. New approach to quantifying anatomical curvatures using high-resolution polynomial curve fitting (HR-PCF)[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2005,128, 630-638

URL pmid: 15861424 |

| [28] |

Deane AS, Begun DR. Broken fingers: retesting locomotor hypotheses for fossil hominoids using fragmentary proximal phalanges and high-resolution polynomial curve fitting (HR-PCF)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2008,55, 691-701

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.05.005 URL pmid: 18692864 |

| [29] |

Kivell TL, Kibii JM, Churchill SE, Schmid P, Berger LR. Australopithecus sediba hand demonstrates mosaic evolution of locomotor and manipulative abilities[J]. Science, 2011,333, 1411-1417

doi: 10.1126/science.1202625 URL pmid: 21903806 |

| [30] |

Kivell TL, Deane AS, Tocheri MW, Orr CM, Schmid P, Hawks J, Berger LR, Churchill SE. The hand of Homo naledi[J]. Nature Communications, 2015,6, 8431

URL pmid: 26441219 |

| [31] |

Rein TR. The correspondence between proximal phalanx morphology and locomotion: Implications for inferring the locomotor behavior of fossil catarrhines[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2011,146, 435-445

URL pmid: 21953545 |

| [32] |

Rein TR, Harrison T, Zollikofer CPE. Skeletal correlates of quadrupedalism and climbing in the anthropoid forelimb: Implications for inferring locomotion in Miocene catarrhines[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2011,61, 564-574

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.07.005 URL pmid: 21872907 |

| [33] | Congdon KA. Interspecific and ontogenetic variation in proximal pedal phalangeal curvature of great apes (Gorilla gorilla, Pan troglodytes, and Pongo pygmaeus)[J]. International Journal of Primatology, 2012,33(2), 418-427 |

| [34] |

Harcourt-Smith WEH, Throckmorton Z, Congdon KA, Zipfel B, Deane AS, Drapeau MSM, Churchill SE, Berger LR, DeSilva JM. The foot of Homo naledi[J]. Nature Communications, 2015,6, 8432

URL pmid: 26439101 |

| [35] |

Dominguez-Rodrigo M, Pickering TR, Almecija S, Heaton JL, Baquedano E, Mabulla A, Uribelarrea D. Earliest modern human-like hand bone from a new >1.84-million-year-old site at Olduvai in Tanzania[J]. Nature Communications, 2015,6, 7987

doi: 10.1038/ncomms8987 URL pmid: 26285128 |

| [36] | Lanyon LE, Rubin CT. Functional adaptation in skeletal structures [A]. In: Hildebrand M, Bramble DM, Liem KF, Wake DB eds. Functional Vertebrate Morphology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985, 1-25 |

| [37] |

Dodge T, Wanis M, Ayoub R, Zhao LM, Watts NB, Bhattacharya A, Akkus O, Robling A, Yokota H. Mechanical loading, damping, and load-driven bone formation in mouse tibiae[J]. Bone, 2012,51, 810-818

doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.07.021 URL pmid: 22878153 |

| [38] |

Frost HM. Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 1. Redefining Wolff's Law: the bone modeling problem[J]. The Anatomical Record, 1990a,226, 403-413

URL pmid: 2184695 |

| [39] |

Frost HM. Skeletal structural adaptations to mechanical usage (SATMU): 2. Redefining Wolff's Law: the remodeling problem[J]. The Anatomical Record, 1990b,226, 414-422

URL pmid: 2184696 |

| [40] |

Robling AG, Castillo AB, Turner CH. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling[J]. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 2006,8, 455-498

URL pmid: 16834564 |

| [41] |

Bidan CM, Kommareddy KP, Rumpler M, Kollmannsberger P, Brechet YJM, Fratzl P, Dunlop JWC. How linear tension converts to curvature: geometric control of bone tissue growth[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012,7(5), e36336

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036336 URL pmid: 22606256 |

| [42] | Oxnard CE. Form and pattern in human evolution: some mathematical, physical, and engineering approaches [M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973, 1-218 |

| [43] | Sarmiento EE. Anatomy of the hominoid wrist joint: its evolutionary and functional implications[J]. International Journal of Primatology, 1988,9, 281-345 |

| [44] | Richmond BG. Ontogeny and biomechanics of phalangeal form in primates[D]. Stony Brook: State University of New York, 1998, 1-240 |

| [45] |

Richmond BG. Biomechanics of phalangeal curvature[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2007,53, 678-690

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.05.011 URL pmid: 17761213 |

| [46] |

Biewener AA. Allometry of quadrupedal locomotion: the scaling of duty factor, bone curvature and limb orientation to body size[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 1983,105, 147-171

URL pmid: 6619724 |

| [47] | Swartz SM. Curvature of the forelimb bones of anthropoid primates: overall allometric patterns and specializations in suspensory species[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1990,83, 477-498 |

| [48] |

Godfrey LR, Jungers WL, Wunderlich RE, Richmond BG. Reappraisal of the postcranium of Hadropithecus (Primates, Indroidea)[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1997,103, 529-556

doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199708)103:4<529::AID-AJPA9>3.0.CO;2-H URL pmid: 9292169 |

| [49] | Richmond BG, Whalen M. Forelimb function, bone curvature and phylogeny of Sivapithecus [A]. In: de Bonis L, Koufos GD, Andrews P eds. Phylogeny of the Neogene hominoid primates of Eurasia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, 326-348 |

| [50] | Susman RL. Functional and evolutionary morphology of hominoid manual rays II-V[D]. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 1976, 1-372 |

| [51] | Bookstein FL. A statistical-method for biological shape comparisons[J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 1984,107, 475-520 |

| [52] | Bookstein FL. Morphometric tools for landmark data [M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991, 1-435 |

| [53] | Xu Q, Lu Q. Lufengpithecus lufengensis - an early member of Hominidae [M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2008, 1-224 |

| [54] | Wu R, Xu Q, Lu Q. Relationship between Lufeng Sivapithecus and Ramapithecus and their phylogenetic position[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1986,5(1), 1-30 |

| [55] |

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis[J]. Nature Methods, 2012,9, 671-675

URL pmid: 22930834 |

| [56] | Adams DC, Rohlf FJ, Slice DE. A field comes of age: geometric morphometrics in the 21st century[J]. Hystrix, 2013,24, 7-14 |

| [57] | R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [EB/OL]. 2020, URL https://www.R-project.org/. |

| [58] | Claude J. Morphometrics with R (Use R)[M]. New York: Springer, 2008, 1-316 |

| [59] | Bookstein FL. Size and shape spaces for landmark data in two dimensions[J]. Statistical Science, 1986,1, 181-242 |

| [60] |

Koo TK, Li MY. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research[J]. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 2016,15, 155-163

doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 URL pmid: 27330520 |

| [61] | Carpenter CR. A field study in Siam of the behavior and social relations of the gibbon (Hylobates lar) [M]. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1940, 1-212 |

| [62] | Fleagle JG. Locomotion and posture of the Malayan siamang and implications for hominoid evolution[J]. Folia Primatologica, 1976,26, 245-269 |

| [63] | Fleagle JG. Locomotion and posture [A]. In: Chivers DJ ed. Malayan Forest Primates. New York: Springer, 1980, 191-207 |

| [64] |

Fan PF, Scott MB, Fei HL, Ma CY. Locomotion behavior of Cao Vit gibbon (Nomascus nasutus) living in karst forest in Bangliang Nature Reserve, Guangxi, China[J]. Integrative Zoology, 2013,8, 356-364

doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2012.00300.x URL pmid: 24344959 |

| [65] | Gittins SP. Use of the forest canopy by the agile gibbon[J]. Folia Primatologica, 1983,40, 134-144 |

| [66] | Schmidt M. Locomotion and postural behavior[J]. Advances in Science and Research, 2010,5, 23-39 |

| [67] |

Alba DM, Almécija S, Moyà-Solà S. Locomotor inferences in Pierolapithecus and Hispanopithecus: Reply to Deane and Begun (2008)[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2010,59, 143-149

doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.02.002 URL pmid: 20510436 |

| [68] |

Matarazzo S. Knuckle walking signal in the manual digits of Pan and Gorilla[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2008,135, 27-33

doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20701 URL pmid: 17787000 |

| [69] |

Qi GQ, Dong W, Zheng L, Zhao L, Gao F, Yue L, Zhang Y. Taxonomy, age and environment status of the Yuanmou hominoids[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2006,51, 704-712

doi: 10.1007/s11434-006-0704-5 URL |

| [70] | Dong W, Qi GQ. Hominoid-producing localities and biostratigraphy in Yunnan [A]. In: Wang X, Flynn LJ, Fortelius M eds. Fossil mammals of Asia: Neogene biostratigraphy and chronology. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013, 293-313 |

| [71] | Lin Y, Wang S, Guo Z, Zhang L. The first discovery of the radius of Sivapithecus lufengensis in China[J]. Geological Review, 1987,33, 1-4 |

| [72] | Xiao M. The fossil scapula from the Lufeng hominoid site [A]. In: Collected Works of the 30th Anniversary of the Yunnan Provincial Museum. Kunming: Yunnan Provincial Museum, 1981, 41-44 |

| [73] |

Harrison T, Ji X, Su D. On the systematic status of the late Neogene hominoids from Yunnan Province, China[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2002,43, 207-227

doi: 10.1006/jhev.2002.0570 URL |

| [74] | Begun DR. Fossil record of Miocene hominoids [A]. In: Henke W, Tattersall I eds. Handbook of Paleoanthropology. New York: Springer, 2015, 1261-1332 |

| [75] | Nakatsukasa M, Almécija S, Begun DR. The hands of Miocene hominoids [A]. In: Kivell T, Lemelin P, Richmond B, Schmitt D eds. The evolution of the primate hand: Perspectives from anatomical, developmental, functional and paleontological evidence. New York: Springer, 2016, 485-514 |

| [76] | Zheng L. New Lufengpithecus hudienensis fossils discovered within the framework of State Key Project of the 9th five year plan [A]. In: Qi GQ, Dong W eds. Lufengpithecus hudienensis site. Beijing: Science Press, 2006, 41- 74, 281-292 |

| [77] | Preuschoft H. Functional anatomy of the upper extremity [A]. In: Bourne GH ed. The chimpanzee, Vol. 6. Basel: Karger, 1973, 34-120 |

| [78] | Sun X, Wu Y. Paleoenvironment during the time of Ramapithecus lufengensis[J]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 1980,18, 247-255 |

| [79] | Badgley C, Qi GQ, Chen W, Han D. Paleoecology of a Miocene, tropical, upland fauna: Lufeng, China[J]. National geographic research, 1988,4, 178-195 |

| [80] | Qi GQ. The environment and ecology of the Lufeng hominoids[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1993,24, 3-11 |

| [81] | Cheng YM, Wang YF, Li CS. Late Miocene wood flora associated with the Yuanmou hominoid fauna from Yunnan, southwestern China and its palaeoenvironmental implication[J]. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2014,3, 323-330 |

| [82] | Chang L, Guo Z, Deng C, et al. Pollen evidence of the paleoenvironments of Lufengpithecus lufengensis in the Zhaotong Basin, southeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2015,435, 95-104 |

| [1] | 张颖奇, Terry HARRISON. 化石人猿超科成员指趾骨弯曲程度与位移行为[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(04): 659-673. |

| [2] | 王翠斌;赵凌霞. 禄丰古猿前部牙齿的釉面横纹与牙冠形成时间[J]. 人类学学报, 2016, 35(01): 101-108. |

| [3] | 王翠斌;赵凌霞. 禄丰古猿带状牙釉质发育不全的再观察[J]. 人类学学报, 2015, 34(04): 544-552. |

| [4] | . 深切悼念吴汝康院士[J]. 人类学学报, 2006, 25(04): 263-266. |

| [5] | 赵凌霞. 禄丰古猿牙齿釉质发育不全的观察研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2004, 23(02): 111-118. |

| [6] | 刘武,郑良,Alan Walker. 元谋古猿下颌臼齿三维立体特征[J]. 人类学学报, 2001, 20(03): 163-177. |

| [7] | 陆庆五,赵凌霞. 禄丰古猿下颌恒齿萌出顺序的研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2000, 19(01): 11-85. |

| [8] | 赵凌霞,欧阳涟,陆庆五. 禄丰古猿(Lufengpithecus lufengensis)牙齿釉质生长线与个体发育问题研究[J]. 人类学学报, 1999, 18(02): 102-108. |

| [9] | 姜础. 元谋小河村古猿上颌骨化石的初步研究[J]. 人类学学报, 1996, 15(01): 36-40. |

| [10] | 陆庆五. 禄丰古猿幼年下颌骨的研究[J]. 人类学学报, 1995, 14(02): 93-189. |

| [11] | 吴汝康. 人类起源研究的新进展和新问题[J]. 人类学学报, 1994, 13(04): 353-373. |

| [12] | 吴汝康. 中国古人类研究在人类进化史中的作用——纪念北京猿人第一头盖骨发现六十周年[J]. 人类学学报, 1989, 8(04): 293-300. |

| [13] | . 消息与动态[J]. 人类学学报, 1988, 7(01): 95-96. |

| [14] | 陆庆五,赵中义. 禄丰古猿雌性头像的复原[J]. 人类学学报, 1988, 7(01): 9-16、101. |

| [15] | 吴汝康. 禄丰大猿化石分类的修订[J]. 人类学学报, 1987, 6(04): 265-271. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||

京ICP证05002819号-3

京ICP证05002819号-3