收稿日期: 2020-04-22

修回日期: 2020-06-12

网络出版日期: 2020-08-31

基金资助

中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(B类: XDB26000000);郑州大学“中华文明根系研究”(XKZDJC202006);国家自然科学基金(41672024);国家科技基础性工作专项(2014FY110300)

Fire for hominin survivals in prehistory

Received date: 2020-04-22

Revised date: 2020-06-12

Online published: 2020-08-31

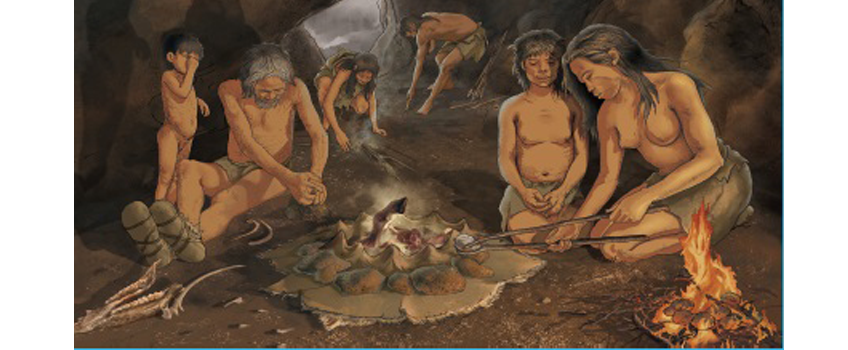

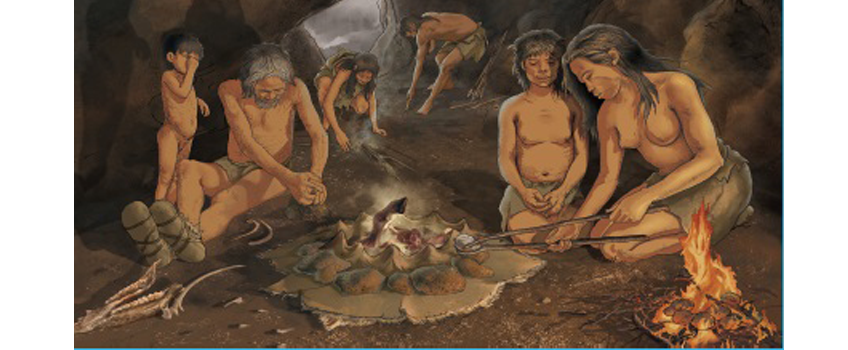

用火是人类独有的行为能力,对人类的生存演化至关重要。用火熟食改善了人类的营养,导致人类生物特性发生一系列改变,人口、行为、社会关系和生存方式也发生相应变化。用火使人类获得更多的生存资源,并帮助人类改变工具与用具的材料特性,如对石料做热处理,进而发明了陶器和金属工具,开启了文明的历程。人类与火的互动是一个长期、曲折的过程,经历了偶尔利用自然火、时断时续对火控制和使用、有效保存火种乃至人工取火形成用火的日常习惯,进而发展到现代无所不在、不可或缺的复杂用火。人类用火被认为始于直立人的诞生,但目前提取到的证据指向150万年前。早期人类用火证据的提取和论证存在极大的困难和挑战,需要精细的野外工作,做高精度的遗址埋藏和遗物遗迹的空间分析,须采用现代科技手段和模拟实验对地层沉积物和燃烧物证做微形态、成分、色度、磁化率、微体植物化石等尽可能多的宏观和微观分析,排除自然因素的干扰,这样得出的结论才会坚实可信。本文介绍了人类用火的历史、作用和对用火证据提取与分析的思路、方法与技术,通过一系列案例阐述人类用火的方式、发展演化过程和考古学家为破译远古人类用火的谜团所做的努力和取得的成果,以期对这项意义重大但常被忽视的研究起到推动作用。

高星 . 史前人类的生存之火[J]. 人类学学报, 2020 , 39(03) : 333 -348 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2020.0008

The paper made an in-depth review on the history of academic research on hominin use of fire. It discussed the significance of fire-use to human evolution and development, presented different hypotheses on the origins of controlled use of fire by human ancestors, and used a series of case-studies to demonstrate the way fire-use evidences were collected and analyzed, and the complicated developmental process of fire-use in human history. Controlled use of fire is a unique behavior and capacity of human beings, and it has played an essential role on hominid survival and evolution. The use of fire led to cooked foods and made nutrition more easily be digested, which in turn brought about a series of biological adjustments and changes in demography, behavioral patterns, survival strategies and social structures to our species. Fire helped hominins procure more resources and modify physical properties of imperative materials, such as heat treatment on lithic raw materials, and gradually brought about the invention of pottery and metal utensils, and eventually human civilization. The history of human-fire interaction is a long and tortuous process, from the occasional use of natural fire, controlled use of fire on and off for hundreds of thousands of years, effective preservation of fire seeds, the making of fire and habitual use of fire, to the omnipresent, indispensable and complex ways of fire-use today. It has been proposed that hominid fire-use history began with the emergence of Homo erectus, but the current available reliable evidence pointed to the time node of ca. 1.5 MaBP. The detection and verification of fire-use evidence of early stage are difficult and challenging, requiring delicate and detailed field excavation and recording, high-resolution taphonomic and spatial information, and all applicable analyses with state-of-the-art technologies. Possible factors of natural agencies in producing fire remains, such as natural fire and post-depositional disturbance, have to be evaluated and terminated. Only after such careful data collection and comprehensive analysis, the evidence presented and conclusions reached can be convincing and accepted.

| [1] | Richard Wrangham, Kevin Pariseau. Catching fire: How cooking made us human[J]. Nature, 2009,20(4):447-449 |

| [2] | Lynn DC. Hearth and Campfire Influences on Arterial Blood Pressure: Defraying the Costs of the Social Brain through Fireside Relaxation[J]. Evolutionary Psychology, 2014,12(5):983-1003 |

| [3] | SJill D Pruetz, Nicole M Herzog. Savanna Chimpanzees at Fongoli, Senegal, Navigate a Fire Landscape[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):337-350 |

| [4] | Nicole M Herzog, Earl R Keefe, Christopher H Parker, et al. What’s Burning got to do With it? Primate Foraging Opportunities in Fire-Modified Landscapes[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2016,159:432-441 |

| [5] | Wrangham Richard W, Nancy L Conklin-Brittain. The biological significance of cooking in human evolution[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, A, 2003,136:35-46 |

| [6] | Wrangham Richard W, Rachel Carmody. Human adaptation to the control of fire[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2010,19:187-199 |

| [7] | Brain CK, A Sillen. Evidence from the Swartkrans cave for the earliest use of fire[J]. Nature, 1988,336:464-466 |

| [8] | Gowlett JAJ, JWK Harris, D Walton, et al. Early archaeological sites, hominid remains and traces of fire from Chesowanjia, Kenya[J]. Nature, 1981,294:125-129 |

| [9] | 贾兰坡, 王建. 西侯度——山西更新世早期古文化遗址[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 1978 |

| [10] | 袁振新, 林一朴, 周国兴, 文本亨. 云南元谋人化石产地的综合研究[A].中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所编.古人类论文集[C]. 北京: 科学出版社, 197:94-98 |

| [11] | Michael Chazan. Toward a Long Prehistory of Fire[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(Supplement 16):351-359 |

| [12] | Black D. Evidence of the use of fire by Sinanthropus[J]. Bulletin for Geological Society of China, 1931,11:107-108 |

| [13] | Steven R James, RW Dennell, Allan S Gilbert, et al. Hominid Use of Fire in the Lower and Middle Pleistocene: A Review of the Evidence[J]. Current Anthropology, 1989,30(1):1-26 |

| [14] | 周振宇, 关莹, 王春雪, 等. 旧石器时代的火塘与古人类用火[J]. 人类学学报, 2012,31(1):24-40 |

| [15] | Weiner S Ofer Bar-Yosef, Paul Goldberg, Xu , QQ . et al. Evidence for the use of fire at Zhoukoudian[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2000,19(supplement):218-223 |

| [16] | Goren Inbar N, Alperson N, Kislev ME, et al. Werker. Evidence of hominin control of fire at GBY, Israel[J]. Science, 2004,304(5671):725-727 |

| [17] | Nira Alperson-Afil. Continual fire-making by Hominins at Gesher Benot Ya‘aqov, Israel[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2008,27:1733-1739 |

| [18] | Berna F, Goldberg P, Horwitz LK, et al. Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of ences of the United States of America, 2012,109(20):7593-7594 |

| [19] | Hlubik S, Berna F, Feibel C, et al. Researching the Nature of Fire at 1.5 Mya on the Site of FxJj20 AB, Koobi Fora, Kenya, Using High-Resolution Spatial Analysis and FTIR Spectrometry[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):243-257 |

| [20] | Roebroeks Wil, Paola Villa. On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 2011,108(13):5209-5214 |

| [21] | 高星, 张双权, 张乐, 等. 关于北京猿人用火的证据:研究历史、争议与新进展[J]. 人类学学报, 2016,35(4):481-492 |

| [22] | 张森水. 周口店遗址志[M]. 北京: 北京出版社, 2004 |

| [23] | Harold L Dibble, Aylar Abodolahzadeh, Vera Aldeias, et al. How Did Hominins Adapt to Ice Age Europe without Fire?[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):278-287 |

| [24] | Goldberg P, Bar Yosef O. Site Formation Processes in Kebara and Hayonim Caves and Their Significance in Levantine Prehistoric Caves[M]// Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia. Springer US, 2002. |

| [25] | Shimelmitz R, Kuhn SL, Jelinek AJ, et al. “Fire at will”: the emergence of habitual fire use 350,000 years ago[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2014,77(S1):196-203 |

| [26] | Karkanas P, Shahack Gross R, Ayalon A, et al. Evidence for habitual use of fire at the end of the Lower Paleolithic: Site-formation processes at Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2007,53(2):197-212 |

| [27] | Blasco R, Rosell J, Arilla M, et al. Bone marrow storage and delayed consumption at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel (420 to 200 ka)[J]. Science Advances, 2019,5(10):eaav9822 |

| [28] | Ran Barkai, Jordi Rosell, Ruth Blasco, et al. Fire for a reason: Barbecue at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S16):314-328 |

| [29] | Sorensen AC, Claud E, Soressi M. Neandertal fire-making technology inferred from microwear analysis[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018,8:10065, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-28342-9 |

| [30] | Brown KS, Marean CW, Herriés A, et al. Fire as an engineering tool of early modern humans[J]. Science, 2009,325:859-862 |

| [31] | Copeland L. The Middle Paleolithic flint industry of Ras el-Kelb[A]. In: Copeland L, Moloney N, eds. The Mourterian Site of Ras el-Kelb, Lebanon[M]. Oxford: BAR, 1998: 73-101 |

| [32] | Duttine MP. Effects of thermal treatment on TL and EPR of flints and their importance in TL-Dating: Application to French Mousterian sites of Les Forets (Dordogne) and Jiboui (Drome)[J]. Radiat Meas, 2005,39:375-385 |

| [33] | Domanski M, Webb J. A review of heat treatment research[J]. Lithic Technology, 2007,32:153-194 |

| [34] | 周振宇, 关莹, 高星, 等. 水洞沟遗址的石料热处理现象及其反映的早期现代人行为[J]. 科学通报, 2013,58(9):815-824 |

| [35] | 邵亚琪, 郇勇, 代玉静, 等. 热处理对水洞沟遗址石器原料力学性能的影响[J]. 人类学学报, 2015,34(3):330-337 |

| [36] | Yuichi Nakazawa, Lawrence G Straus, Manuel R Gonza′lez-Morales, et al. On stone-boiling technology in the Upper Paleolithic: behavioral implications from an Early Magdalenian hearth in El Miro′n Cave, Cantabria, Spain[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009,36:684-693 |

| [37] | Binford LR. Dimensional analysis of behavior and site structure: learning from Eskimo hunting stand[J]. American Antiquity, 1978,43:330-361 |

| [38] | Stiner MC. Zooarchaeological evidence for resource intensification in Algarve, southern Portugal[M]. Promontoria: Revista do Departamento de Histo′ ria, Arqueologia e Patrimo′ nio da Universidade do Algarve, 2003,1:27-61 |

| [39] | Bicho N, Stiner M, Lindly J, et al. Preliminary results from the Upper Paleolithic site of Vale Boi, southwestern Portugal[J]. Journal of Iberian Archaeology, 2003,5:51-66 |

| [40] | 高星, 王惠民, 刘德成, 等. 水洞沟第12地点古人类用火研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2009,28(4):229-336 |

| [41] | 张乐, 张双权, 徐欣, 等. 中国更新世末全新世初广谱革命的新视角:水洞沟第 12 地点的动物考古学研究[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2013,43(4):628-633 |

| [42] | Thoms AV. Rocks of ages: Propagation of hot-rock cookery in western North America[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2009,36:573-591 |

| [43] | Kelly RL. The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter Gatherer Lifeways[M]. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995 |

| [44] | Stiner MC, Munro N. The tortoise and the hare small-game use, thebroad-spectrum revolution, and Paleolithic demography[J]. Current Anthropology, 2000,41:39-74 |

| [45] | Zeder MA. The Broad Spectrum Revolution at 40: Resource diversity, intensification, and an alternative to optimal foraging explanations[J]. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2012,31:241-264 |

| [46] | Douglas W Bird, Rebecca BB Bird, Brian F Codding. Pyrodiversity and the Anthropocene: The role of fire in the broad spectrum revolution[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2016,25:105-116 |

| [47] | Wu Xiaohong, Zhang Chi, Paul Goldberg, et al. Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China[J]. Science, 2012,336:1696-1700 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |