收稿日期: 2018-12-17

修回日期: 2019-05-28

网络出版日期: 2020-09-10

Bone needles in China and their implications for Late Pleistocene hominin dispersals

Received date: 2018-12-17

Revised date: 2019-05-28

Online published: 2020-09-10

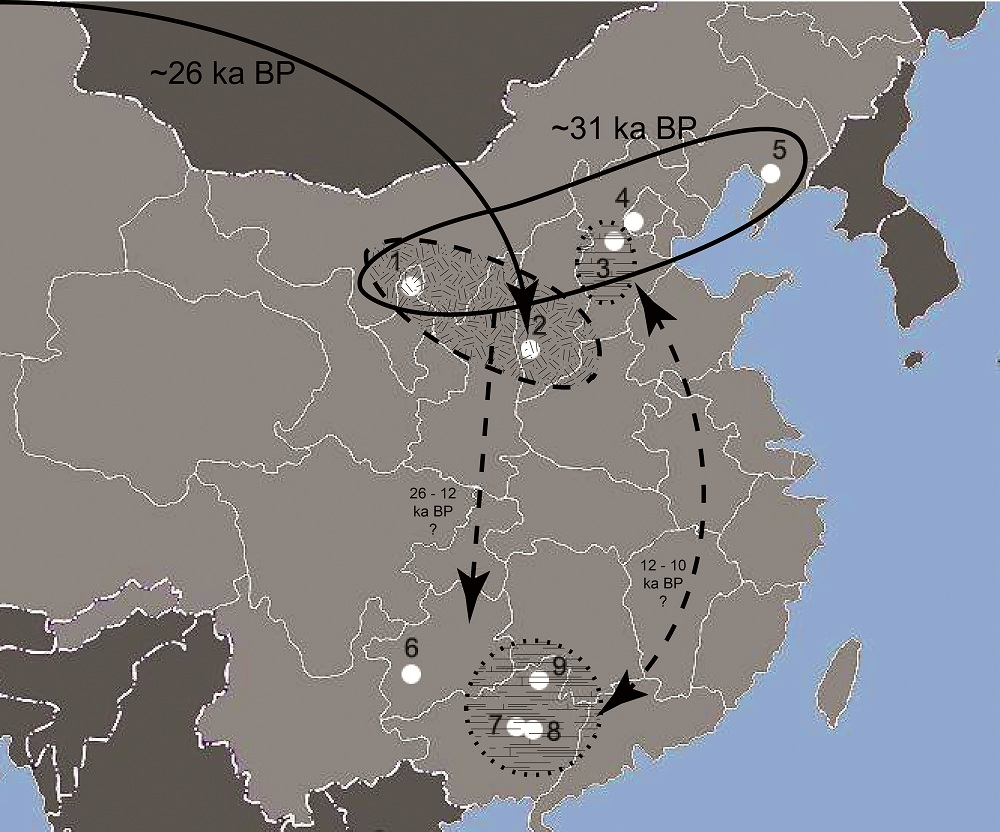

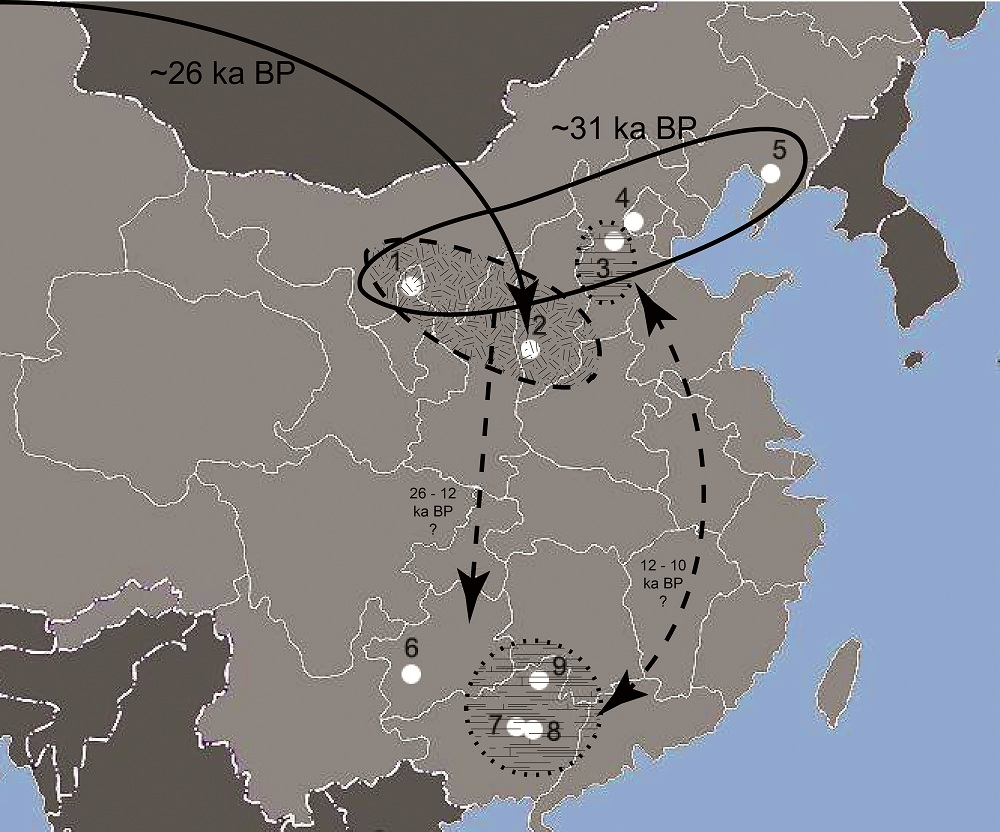

在最近的一篇文章中,由d’Errico教授率领的来自中国、法国、德国研究者的工作表明,世界上最早的骨针出现于西伯利亚和中国北方地区,且这两个地区的骨针可能是独立起源。中国考古学的纪录为这一观点提供了更多的新证据。本文将这一工具类型与石器技术和环境背景结合考察,探讨更新世晚期后半段发生的人群的扩散。我们通过材料的梳理证明,中国北方地区的骨针,是出现于距今31000年前的一次技术创新,这一技术创新以石核-石片技术为代表的中国旧石器晚期的到来为背景。距今25000年,一种新形制的骨针出现。这些骨针形制扁平,与细石叶技术同时出现。这可能反映了欧亚大陆西方人群的东迁,这些人群带来了细石叶技术。更新世末,骨针更加多样化,这意味着他们可能有多种用途。在晚冰期末段,中国北方地区的骨针不仅与细石叶技术共出,同时也与石核、石片和陶器共出。在中国南方地区,在距今12000年前,骨针的出现与石核-石片技术同时出现。南方地区的骨针或是本地的的发明,或由末次冰期前北方人群的南迁带来的。长江以南地区,骨针与石核、石片和陶器在更新世晚期同时出现。更新世晚期中国南北方地区同时出现的这一工具组合,即石核、石片、陶器和骨针,预示着南北方地区在更新世晚期和全新世早期可能存在着长距离的人群的移动和文化的交流。

鲁可 . 中国的骨针及其对晚更新世人类扩散的指示意义[J]. 人类学学报, 2019 , 38(03) : 362 -372 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2019.0033

In a recent article, a team of Chinese, French, Canadian, and Czech researchers led by d’Errico suggested the earliest bone needles were manufactured in Siberia and northern China, and were invented independently in both regions. Here, the Chinese archaeological record is reviewed to provide more details on this claim. The occurrence of this tool type is correlated with the associated lithic technologies and the environmental conditions in order to investigate the dispersal events that took place during the second half of the Late Pleistocene. The review suggests the manufacture of needles represents an indigenous innovation that appears in northern China circa 31 kaBP on the onset of the Chinese Late Palaeolithic alongside stone tools attributed to the core-and-flake technology. As of 25 kaBP, a new form of needle is introduced in the archaeological record. These needles are flat and they appear with stone tools attributed to the microblade technology. This evidence likely signals the migration of a populations bringing with them blade technologies from western Eurasia. At the end of the Pleistocene, bone needles are more diversified, which suggests they were used in a variety of tasks. During the late-Tardiglacial, bone needles are found in northern China both in contexts that yielded microblade technology as well as core-and-flake technology with ceramic. In southern China, the first bone needles appear alongside core-and-flake technology around 12 kaBP. The first appearance of this tool type in southern China could either be the result of a convergent innovation or the southward migration of prehistoric populations that lived in northern China prior to the Last Glacial Maximum. South of the Yangzi river, bone needles are manufactured at the end of the Pleistocene in contexts attributed to the core-and-flake technology with ceramic. The presence of the same toolkit in both northern and southern China at the end of the Pleistocene, i.e., core-and-flake technology with ceramic and bone needles, raises the question of potential long-distance population movements and cultural influences across North and South China at the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene.

| [1] | Gilligan I. The prehistoric development of clothing: Archaeological implications of a thermal model[J]. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 2010,17(1):15-80 |

| [2] | Albes E. The Fuegians and their cold land of fire[J]. Bulletin of the Pan American Union, 1917,XLIV(1):1-21 |

| [3] | Lloyd GT. Thirty-three years in Tasmania and Victoria[M]. London: Houlston and Wright, 1862 |

| [4] | d’Errico F, Doyon L, Zhang SQ, et al. The origin and evolution of sewing technologies in Eurasia and North America[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018,125:71-86 |

| [5] | Stordeur-Yedid D. Les aiguilles à chas au Paléolithique. Gallia Préhistorique Supplément XIII[M]. Paris: éditions du CNRS, 1979 |

| [6] | Bird C, Beeck C. Bone points and spatulae: Salvage ethnography in Southwest Australia[J]. Archaeology & Physical Anthropology in Oceanian, 1980,15(3):168-171 |

| [7] | Lyman RL. North American Paleoindian eyed bone needles: Morphometrics, sewing, and site structure[J]. American Antiquity, 2015,80(1):146-160 |

| [8] | Vanhaeren M, d’Errico F. La parure de l’enfant de la Madeleine (fouilles Peyrony). Un nouveau regard sur l’enfance au Paléolithique supérieur[J]. PALEO. Revue d’archéologie préhistorique, 2001,13:201-240 |

| [9] | Wilder E. Secrets of Eskimo skin sewing[M]. Anchorage: Alaska Northwest Pub. Co., 1976 |

| [10] | Chen F, Li F, Wang H, et al. Excavation report of the second location of Shuidonggou site in Ningxia[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2012,31(4):317-333(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [11] | Gao X, Wang H, Pei S, et al. Shuidonggou - Excavation and research (2003-2007) report[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2013(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [12] | Li F, Bae CJ, Ramsey CB, et al. Re-dating Zhoukoudian Upper Cave, northern China and its regional significance[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2018,121:170-177 |

| [13] | Pei WC. The Upper Cave industry of Chokoutien[J]. Palaeontologica Sinica(Series D), 1939, 1-58 |

| [14] | Huang W, Zhang Z, Fu R, et al. Bone products and decorations in Haicheng Xiaogushan[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1986,5(3):259-266(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [15] | Norton CJ, Jin JJH. The evolution of modern human behavior in East Asia: Current perspectives[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 2009,18(6):247-260 |

| [16] | Hedges REM, Housley RA, Law IA, et al. Radiocarbon dates from the Oxford AMS system archaeometry datelist 8[J]. Archaeometry, 1988,30(2):291-305 |

| [17] | Li X. A research on the bone needles of Shizitan site in Paleolithic period and its related problems[D]. Taiyuan: Shanxi University, 2013(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [18] | Song Y, Li X, Wu X, et al. Bone needle fragment in LGM from the Shizitan site (China): Archaeological evidence and experimental study[J]. Quaternary International, 2016,400:140-148 |

| [19] | Zhang Y, Gao X, Pei S, et al. The bone needles from Shuidonggou locality 12 and implications for human subsistence behaviors in North China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016,400(Supplement C):149-157 |

| [20] | Zhang SQ, Doyon L, Zhang Y, et al. Innovation in bone technology and artefact types in the late Upper Palaeolithic of China: Insights from Shuidonggou Locality 12[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2018,93:82-93 |

| [21] | Li J, Qiao Q, Ren X. Excavation to Nanzhuangtou site in Xushui County, Hebei in 1997[J]. Acta Archaeologica Sinica, 2010(3):361-392(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [22] | Mao Y, Cao Z. A preliminary study of the polished bone tools unearthed in 1979 from the Chuandong site in Puding County, Guizhou[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2012,31(4):335-343(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [23] | Zhang S. A brief study of Chuandong prehistoric site (excavated in 1981)[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1995,14(2):132-146(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [24] | Chinese Academy of Social Science Institute of Archaeology, Guanxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Institute of Cultural Relics, Guilin Zengpiyan Site Museum. Zengpiyan in Guilin[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2003(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [25] | Jia L, Qui Z. The Ages of Chopping tools from caves in Guangxi[J]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 1960,2(1):66-70(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [26] | Lotus Cave Science Museum, Beijing Museum of Natural History, Guangxi Wenwu Gongzuodui. Archaeological finds in the Bailian cave site of stone age[J]. Southern Ethnology and Archaeology, 1987: 143-160(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [27] | Qu T, Bar-Yosef O, Wang Y, et al. The Chinese Upper Paleolithic: Geography, chronology, and techno-typology[J]. Journal of Archaeological Research, 2013,21(1):1-73 |

| [28] | Jiang Y, Liu W. Liyuzui site - from Paleolithic to Neolithic[J]. Prehistoric Study, 2004, 232-240(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [29] | Liuzhou Museum, Guangxi Wenwu Gongzuodui. The Neolithic shell mound - Dalongtan Liyuzui site in Liuzhou City[J]. Archaeology, 1983,9:769-775(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [30] | Bae CJ. Late Pleistocene Human Evolution in Eastern Asia: Behavioral Perspectives[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S17):S514-S526 |

| [31] | Bae CJ, Douka K, Petraglia MD. On the origin of modern humans: Asian perspectives[J]. Science, 2017, 6368: eaai9067 |

| [32] | Bae CJ, Li F, Cheng L, et al. Hominin distribution and density patterns in Pleistocene China: Climatic influences[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2018,512:118-131 |

| [33] | Gao X, Zhang X, Yang D, et al. Revisiting the origin of modern humans in China and its implications for global human evolution[J]. Science China Earth Sciences, 2010,53(12):1927-1940 |

| [34] | Gómez Coutouly YA. The Emergence of Pressure Knapping Microblade Technology in Northeast Asia[J]. Radiocarbon, 2018,60(3):821-855 |

| [35] | Martinón-Torres M, Wu X, Bermúdez de Castro JM, et al. Homo sapiens in the Eastern Asian Late Pleistocene[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S17):S434-S448 |

| [36] | Sikora M. A Genomic View of the Pleistocene Population History of Asia[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S17):S397-S405 |

| [37] | Wang Y. Late Pleistocene Human Migrations in China[J]. Current Anthropology, 2017,58(S17):S504-S513 |

| [38] | Feng ZD, Tang LY, Ma YZ, et al. Vegetation variations and associated environmental changes during marine isotope stage 3 in the western part of the Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2007,246(2):278-291 |

| [39] | Gao X. Explanations of Typological Variability in Paleolithic Remains from Zhoukoudian Locality 15, China[D]. Tucson: University of Arizona, 2000 |

| [40] | Gao X, Norton CJ. A critique of the Chinese ‘Middle Palaeolithic’[J]. Antiquity, 2002,76(292):397-412 |

| [41] | Li Y, Bodin é. Variabilité et homogénéité des modes de débitage en Chine entre 300 000 et 50 000 ans[J]. L’Anthropologie, 2013,117(5):459-493 |

| [42] | Zhang S. The regional development and interaction of Paleolithic industries in northern China[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1990,9:322-333(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [43] | Derevianko AP. Three scenarios of the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition. Scenario 1: The Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in Northern Asia[J]. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, 2010,38(3):2-32 |

| [44] | Derevianko AP, Shunkov MV. Formation of the Upper Paleolithic traditions in the Altai[J]. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia, 2004,3:12-40 |

| [45] | Derevianko AP, Shunkov MV. Development of early human culture in northern Asia[J]. Paleontological Journal, 2009,43(8):881-889 |

| [46] | Derevianko AP, Markin SV, Tabarev AV. The Palaeolithic of Northern Asia[A]. In: Cummings V, Jordan P, Zvelebil M eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, 1-20 |

| [47] | Shalagina AV, Baumann M, Kolobova KA, et al. Bone needles from Upper Paleolithic complexes of the Strashnaya Cave (North-Western Altai)[J]. Theory and Practice of Archaeological Research, 2018,21:89-98 |

| [48] | Ji D, Chen F, Bettinger RL, et al. Human response to the Last Glacial Maximum: Evidence from North China[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2005,24(4):270-282(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [49] | Brantingham PJ, Krivoshapkin AI, Li J, et al. The Initial Upper Paleolithic in Northeast Asia[J]. Current Anthropology, 2001,42(5):735-747 |

| [50] | Lombard M, H?gberg A. The Still Bay points of Apollo 11 Rock Shelter, Namibia: An inter-regional perspective[J]. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, 2018,53(3):312-340 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |