收稿日期: 2019-03-04

修回日期: 2019-04-23

网络出版日期: 2020-09-10

基金资助

国家自然科学基金面上项目(41672023);国家自然科学基金面上项目(41772025);中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(B类)(XDB26000000)

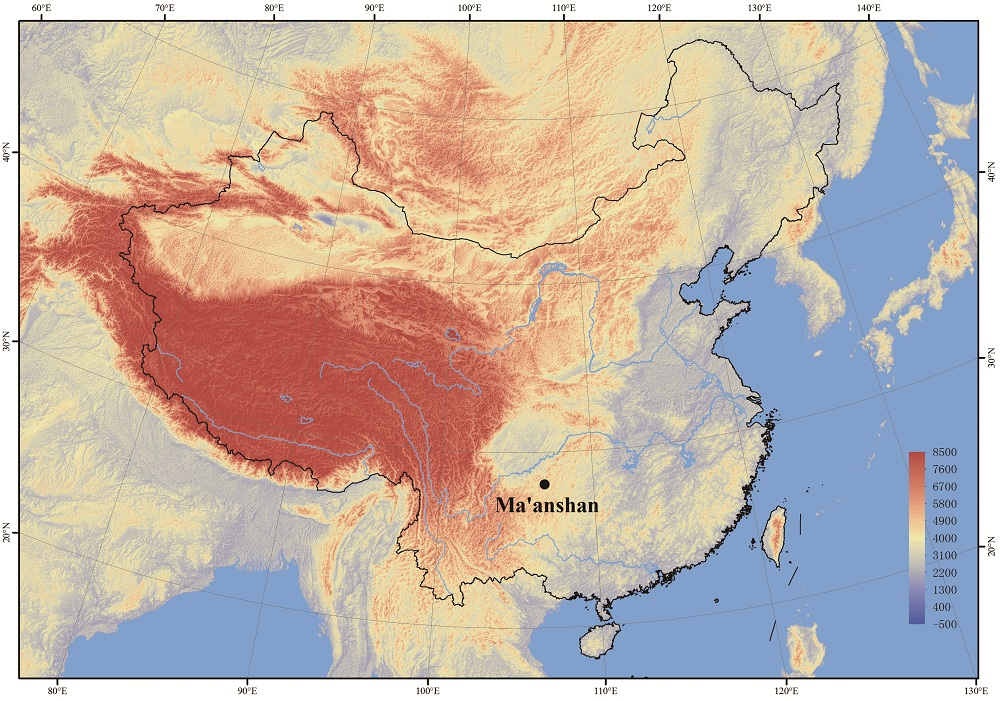

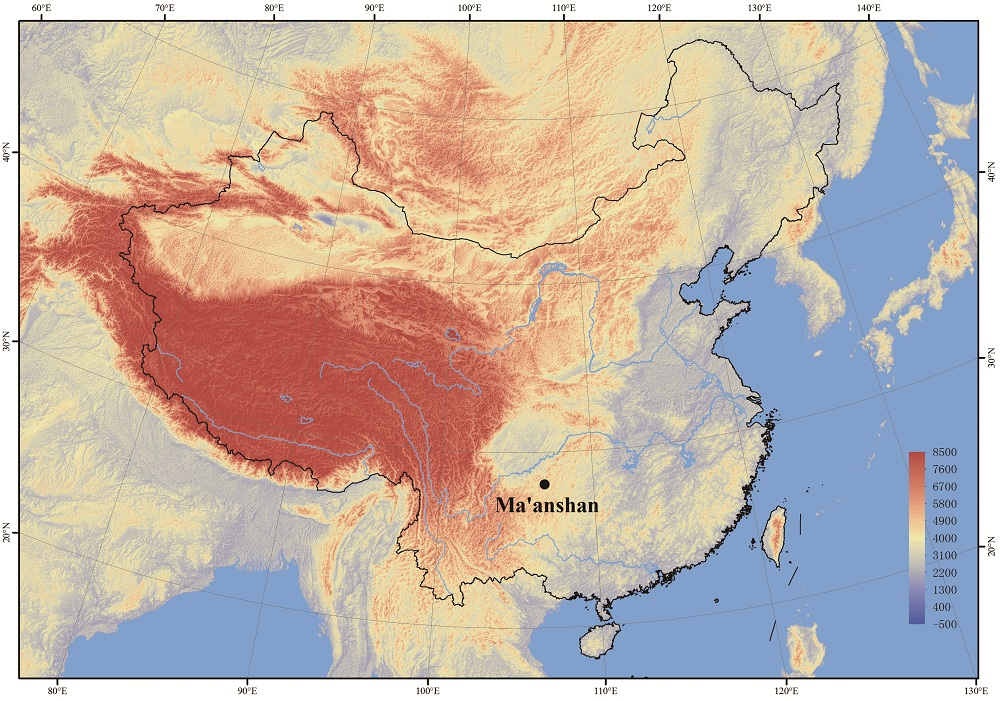

Geographic information system in zooarchaeology: A novel technique in analysis of the faunal remains from the Ma’anshan site, Guizhou, China

Received date: 2019-03-04

Revised date: 2019-04-23

Online published: 2020-09-10

目前,地理信息系统(GIS)在多学科领域的融合方面已经发挥了极为明显的作用。但是,在动物考古学研究中,尤其是在东亚地区,这一手段的使用还明显有所欠缺。本文尝试将这一技术手段应用于贵州马鞍山遗址(距今约43~16 kaBP)出土动物遗存的研究之中。在上千件石制品与数十件骨制品之外,马鞍山遗址还出土有大量的动物化石,从而使其成为检验与实践地理信息系统的一个良好媒介。本文以ArcGIS软件包中的空间分析工具为技术依托,重点对遗址出土的大型动物(包括Bubalus sp 和 Megatapirus augustus) 的骨骼单元分布模式进行了更为准确的统计与分析。本项研究表明,相对于传统方法而言,GIS系统在大型动物遗存的量化统计方面具有独特而重要的价值;此外,这一技术手段还有望在第四纪其他学科的研究中得到发挥与应用。

张乐 , 张双权 , 高星 . 地理信息系统在动物考古学研究中的应用: 以贵州马鞍山遗址出土的动物遗存为例[J]. 人类学学报, 2019 , 38(03) : 407 -418 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2019.0038

Geographic Information System has now found its way into many fields of archaeological research; however, its integration with zooarchaeology is only occasionally practiced, especially in China. In this study, we tentatively adopt this technique in an analysis of the faunal remains from the Ma’anshan site(ca.43-16 kaBP), Guizhou Province of China. Associated with thousands of stone artifacts and dozens of formalized bone tools, this site is exceptional in its excellent preservation of a fairly large bone assemblage. With the assistance of a geoprocessing tool from ArcGIS’s Spatial Analyst extension, skeletal remains of Class III animals(including Bubalus sp. and Megatapirus augustus) from the site are quantified in bulk with maximum precision; meanwhile, patterns in bone element abundance of the two species are visually accentuated. The current study indicates that GIS can be a unique and most potent tool in standardizing and simplifying procedures in analyzing animal bones, especially those of extremely large collections from the Paleolithic sites of China.

| [1] | Gaffney V, Stancic Z. GIS Approaches to Regional Analysis: a Case Study of the Island of Hvar[M]. Ljubljana: Research Institute of the Faculty of Arts & Science, University of Ljubljana, 1991 |

| [2] | Ebert D. Applications of archaeological GIS[J]. Canadian Journal Of Archaeology, 2004,28(2):319-341 |

| [3] | Scianna A, Villa B. GIS applications in archaeology[J]. Archeologia e Calcolatori, 2012,22:337-363 |

| [4] | García-Moreno A, Hutson J, Villaluenga A, et al. Counting sheep without falling asleep: using GIS to calculate the minimum number of skeletal elements(MNE) and other archaeozoological measures at Sch?ningen 13II-4 “Spear Horizon”[A]. In: Giligny F, Djindjian F, Costa L, et al(eds). CAA2014-21st Century Archaeology: Concepts, Methods and Tools. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology[C]. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2015 |

| [5] | Parkinson JA. A GIS image analysis approach to documenting Oldowan hominin carcass acquisition: Evidence from Kanjera South, FLK Zinj, and neotaphonomic models of carnivore bone destruction[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. New York: City University of New York, 2013 |

| [6] | Fischer A. Computerised bone templates as the basis of a practical procedure to record and analyse graphical zooarchaeological data[J]. Revista Electrónica de Arqueología PUCP, 2007,2(1): |

| [7] | Parkinson JA, Plummer T, Hartstone-Rose A. Characterizing felid tooth marking and gross bone damage patterns using GIS image analysis: An experimental feeding study with large felids[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2015,80:114-134 |

| [8] | Herrmann NP, Joanne BD, Jessica CS. Assessment of commingled human remains using a GIS-based and osteological landmark approach[A]. In: Bradley A, John B, eds. Commingled Human Remains: Methods in Recovery, Analysis, and Identification[C]. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 2014, 221-237 |

| [9] | Parkinson JA, Plummer TW, Bose R. A GIS-based approach to documenting large canid damage to bones[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2014,409:57-71 |

| [10] | Abe Y, Marean CW, Nilssen PJ, et al. The Analysis of Cutmarks on Archaeofauna: A Review and Critique of Quantification Procedures, and a New Image-Analysis GIS Approach[J]. American Antiquity, 2002,67(4):643-664 |

| [11] | Marean CW, Abe Y, Nilssen PJ, et al. Estimating the Minimum Number of Skeletal Elements(MNE) in Zooarchaeology: A Review and a New Image-Analysis GIS Approach[J]. American Antiquity, 2001,66(2):333-348 |

| [12] | Nilssen PJ. An actualistic butchery study in South Africa and its implications for reconstructing hominid strategies of carcass acquisition and butchery in the Upper Pleistocene and Plio-Pleistocene[D]. Ph.D Dissertation. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2000 |

| [13] | Lyman RL. Vertebrate Taphonomy[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994: 1-552 |

| [14] | Grayson DK. Quantitative Zooarchaeology: Topics in the Analysis of Archaeological Faunas[M]. Massachusetts: Academic Press, 1984 |

| [15] | Lyman RL. Quantitative Paleozoology[M]. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008 |

| [16] | Marean CW, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Pickering TR. Skeletal element equifinality in zooarchaeology begins with method: the evolution and status of the "shaft critique"[J]. Journal of Taphonomy, 2004,2(2):69-98 |

| [17] | Faith JT, Gordon AD. Skeletal element abundances in archaeofaunal assemblages: economic utility, sample size, and assessment of carcass transport strategies[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007,34(6):872-882 |

| [18] | Faith JT, Domínguez-Rodrigo M, Gordon AD. Long-distance carcass transport at Olduvai Gorge? A quantitative examination of Bed I skeletal element abundances[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2009,56(3):247-256 |

| [19] | Zhang S, Li Z, Zhang Y, et al. Skeletal element distributions of the large herbivores from the Lingjing site, Henan Province, China[J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2012,55(2):246-253 |

| [20] | Faith JT, Thompson JC. Low-survival skeletal elements track attrition, not carcass transport behavior in Quaternary large mammal assemblages[A]. In: Giovas CM, LeFebvre MJ, eds. Zooarchaeology in Practice: Case Studies in Methodology and Interpretation in Archaeofaunal Analysis[C]. Gewerbestrasse: Springer, 2018, 109-126 |

| [21] | Lupo KD. Archaeological skeletal part profiles and differential transport: an ethnoarchaeological example from Hadza bone assemblages[J]. Journal Of Anthropological Archaeology, 2001,20(3):361-378 |

| [22] | Cleghorn N, Marean C. Distinguishing selective transport and in situ attrition: a critical review of analytical approaches[J]. Journal of Taphonomy, 2004,2:43-67 |

| [23] | Cleghorn N, Marean C. The destruction of skeletal elements by carnivores: the growth of a general model for skeletal element destruction and survival in zooarchaeological assemblages[A]. In: Pickering T, Toth N, Schick K, eds. Breathing Life into Fossils: Taphonomic Studies in Honor of CK(Bob) Brain[C]. Indiana: Stone Age Institute Press, 2007, 37-66 |

| [24] | Faith JT. Changes in reindeer body part representation at Grotte XVI, Dordogne, France[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007,34(12):2003-2011 |

| [25] | Bunn HT, Bartram LE, Kroll EM. Variability in bone assemblage formation from Hadza hunting, scavenging, and carcass processing[J]. Journal Of Anthropological Archaeology, 1988,7(4):412-457 |

| [26] | Bartram LE. Perspectives on skeletal part profiles and utility curves from eastern Kalahari ethnoarchaeology[A]. In: Hudson J, ed. From bones to behavior: ethnoarchaeological and experimental contributions to the interpretation of faunal remains[C]. Carbondale: Center for Archaeological Investigations at Southern Illinois University, 1993, 115-137 |

| [27] | Monahan CM. The Hadza Carcass Transport Debate Revisited and its Archaeological Implications[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1998,25(5):405-424 |

| [28] | Marean CW, Cleghorn N. Large Mammal Skeletal Element Transport: Applying Foraging Theory in a Complex Taphonomic System[J]. Journal of Taphonomy, 2003,1(1):15-42 |

| [29] | Zhang Y, Stiner MC, Dennell R, et al. Zooarchaeological perspectives on the Chinese Early and Late Paleolithic from the Ma’anshan site(Guizhou, South China)[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010,37(8):2066-2077 |

| [30] | Zhang SS. A brief report of the tentative excavation in Ma'anshan Paleolithic site[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1988,7(1):64-74(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [31] | Long FX. Analysis of bone fragments from Ma’anshan site, Guizhou[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1992,11(3):216-229(in Chinese with English abstract) |

| [32] | Zhang S, d'Errico F, Backwell LR, et al. Ma'anshan cave and the origin of bone tool technology in China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2016,65:57-69 |

| [33] | Zhang Y, Wang CX, Zhang SQ, et al. A zooarchaeological study of bone assemblages from the Ma'anshan Paleolithic site[J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2010,53(3):395-402 |

| [34] | Brain CK. The Hunters or the Hunted? An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy[M]: University of Chicago Press, 1981: 1-384 |

| [35] | ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop Help 10.3. http://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/10.3/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/equal-to-frequency.htm. Accessed 2018-03-15 |

| [36] | Binford LR. Nunamiut Ethnoarchaeology[M]. New York: Academic Press, 1978: 1-509 |

| [37] | Perkins JD, Daly P. A hunters' village in Neolithic Turkey[J]. Scientific American, 1968,219(5):97-106 |

| [38] | Lyman RL. Bone density and differential survivorship of fossil classes[J]. Journal Of Anthropological Archaeology, 1984,3(4):259-299 |

| [39] | Lam YM, Chen Xb, Pearson OM. Intertaxonomic varibility in patterns of bone density and the differential representation of Bovid, Cervid, and Equid elements in the Archaeological record[J]. American Antiquity, 1999,64(2):343-362 |

| [40] | Klein RG. The mammalian fauna of the Klasies River mouth sites, southern Cape Province, South Africa[J]. South African Archaeological Bulletin, 1976,31(123/124):75-98 |

| [41] | Yellen JE. Cultural patterning in faunal remains: evidence from the Kung Bushmen[A]. In: Ingersoll D, Yellen J, Macdonald W, eds. Experimental archeology[C]. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977, 271-331 |

| [42] | O'Connell JF Hawkes K Blurton JN. Reanalysis of large mammal body part transport among the Hadza[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1990,17(3):301-316 |

| [43] | Abe Y. Hunting and butchery patterns of the Evenki in Northern Transbaikalia, Russia[D]. PhD Dissertation. New York: Stony Brook University, 2005 |

| [44] | Schoville BJ, Otárola-Castillo E. A model of hunter-gatherer skeletal element transport: The effect of prey body size, carriers, and distance[J]. Journal Of Human Evolution, 2014,73:1-14 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |