收稿日期: 2020-03-08

修回日期: 2020-08-20

网络出版日期: 2020-11-25

基金资助

国家自然科学基金(41572161, 41730319)

Evolution of oasis agriculture and civilization exchange since the Bronze age in Transoxiana, Central Asia

Received date: 2020-03-08

Revised date: 2020-08-20

Online published: 2020-11-25

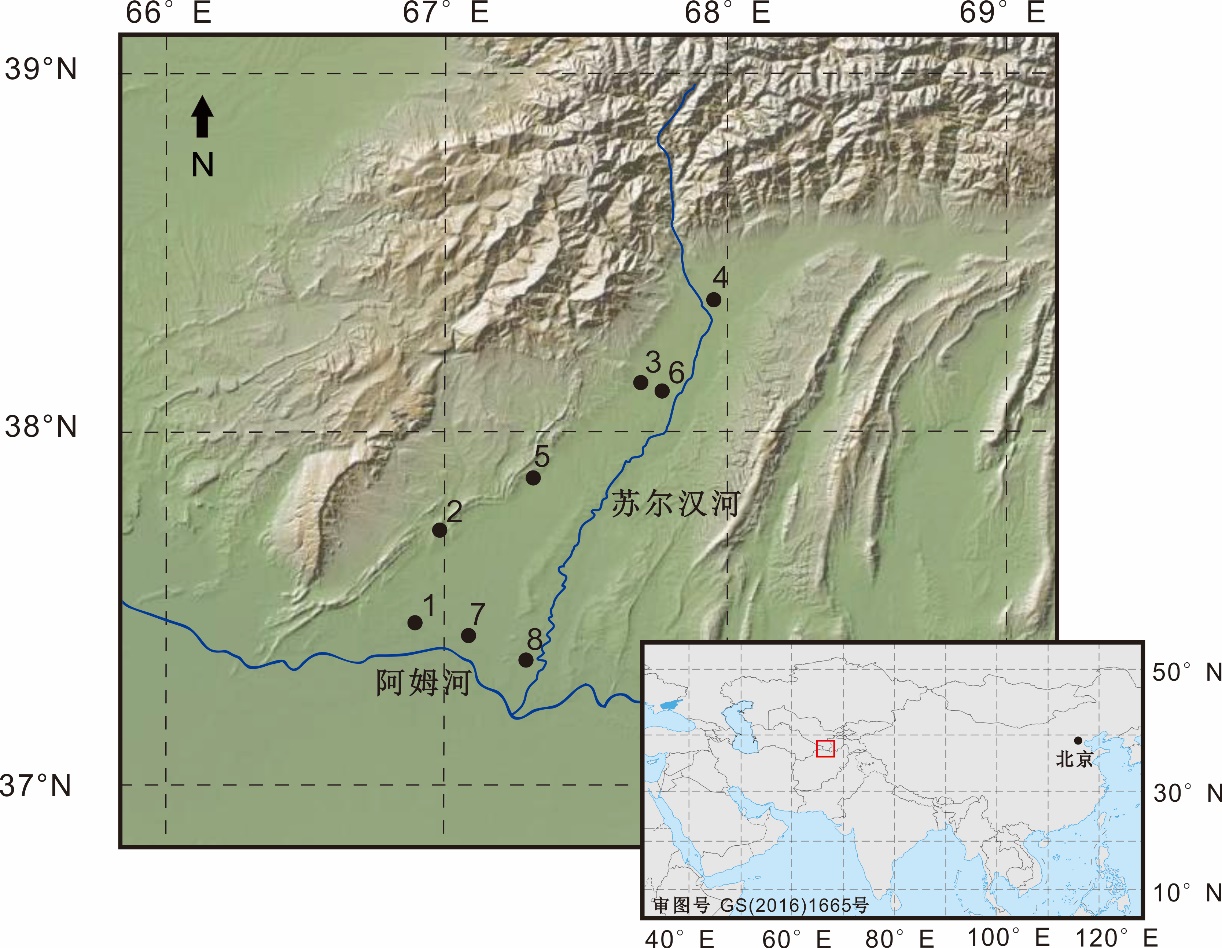

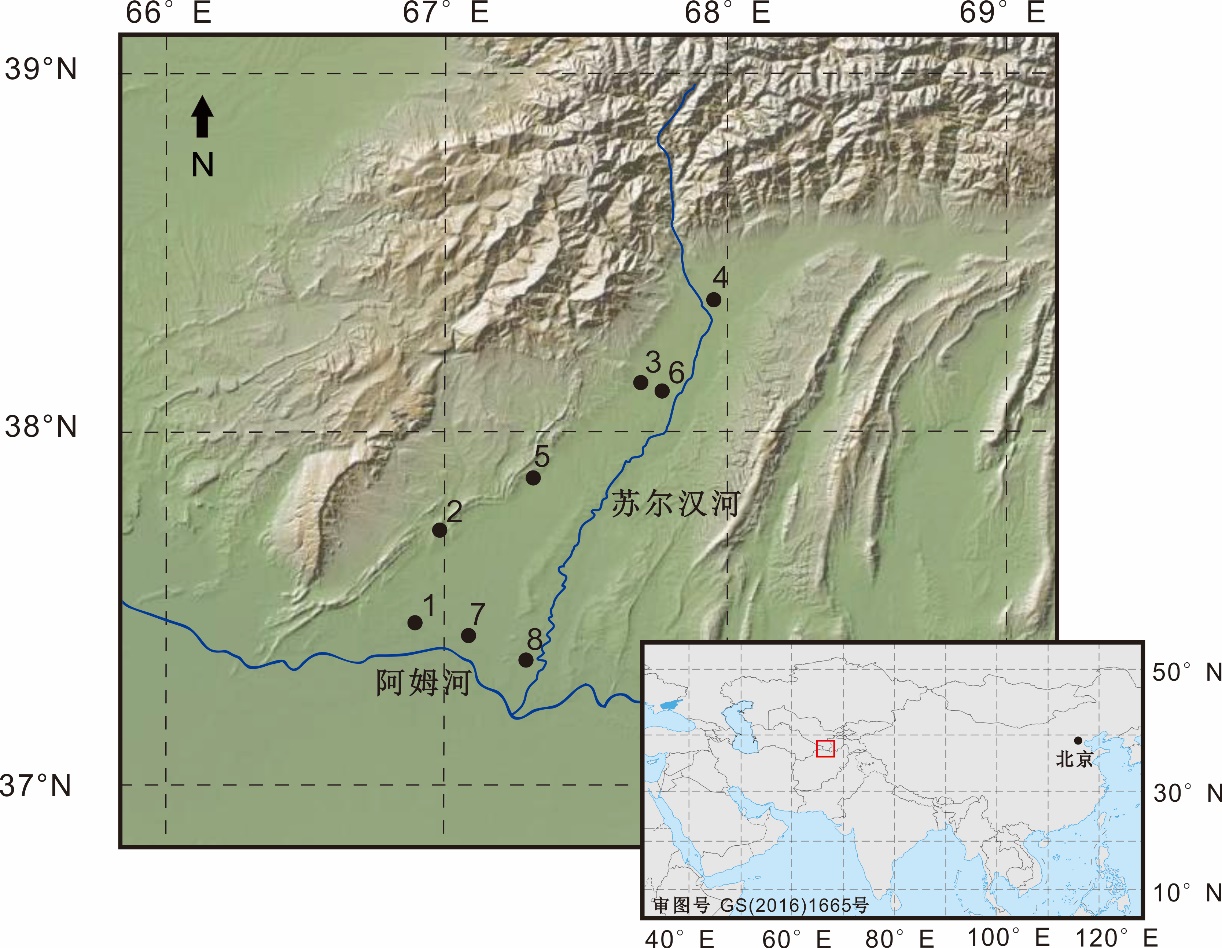

中亚河中地区是东西方文明交流的重要通道,当地干旱的气候对环境变化十分敏感,同时大量保存良好的考古遗迹使得该地区十分适合进行农业活动与文明交流的相关研究。本研究通过年代学与植物考古学方法,对阿姆河流域范围青铜时代晚期至萨珊波斯时期的考古遗址进行研究,尝试重建区内全新世人类农业活动的发展过程,并分析研究4000 BP以来人类的农业活动对环境变化的响应与适应。研究结果显示,河中地区农业的作物构成自4000 BP的青铜时代晚期就已表现出高度的复杂性。虽然在不同的时期不同类型作物的种植比例存在一定的差别,但当地的作物始终以大麦、小麦为主,辅以粟、黍、豆类等谷物及葡萄等果木,自青铜时代晚期形成后这种综合了东西方元素的绿洲农业便保持稳定;后期虽有水稻等作物加入但并没有对已有结构产生较大的影响。本研究为进一步了解中亚内陆干旱-半干旱地区绿洲农业的结构演化及其对环境变化的响应,以及探究不同起源地区作物在亚欧大陆的传播提供了基础资料和新的视角。

陈冠翰 , 周新郢 , 沈慧 , Khasannov Mutalibjon , 马建 , 任萌 , Annaev Tukhtash , 王建新 , 李小强 . 中亚河中地区青铜时代以来绿洲农业的演化与文明的交流[J]. 人类学学报, 2021 , 40(06) : 1108 -1120 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2020.0073

Transoxiana is an ideal place for studying agriculture spread and civilization exchange as the drought local climate meaning that there is sensitivity to environmental changes and good preservation of archaeological materials. This region has always played an important role in communication between eastern and western civilizations in Eurasia. This study combines archaeobotanical and chronological methods in order to reconstruct Holocene agricultural activities and analyze human adaptations to environmental changes in Aum Darya region from 4000 BP (late Bronze Age) to the Sassanid Empire. Results show that the agriculture systems in Transoxiana were highly complexity since 4000 BP. Although different types of crops were planted in different periods, the local oasis agriculture structure composed mainly of barley and wheat, with supplementary foods including common millet, foxtail millet, beans, and fruit such as grapes. Rice and other crops were added in later periods, these foodstuffs did not impact the local agricultural structure. This study provides some details about the evolution of oasis agriculture and human response to environmental changes in Central Asia. It also give us some new perspectives for further study about agricultural spread in Eurasia.

Key words: Transoxiana; Central Asia; Archaeobotany; Agriculture; Holocene

| [1] | Jones M, Hunt H, Lightfoot E, et al. Food globalization in prehistory[J]. World Archaeology, 2011, 43(4):665-675 |

| [2] | Amzallag N. From Metallurgy to Bronze Age Civilizations: The Synthetic Theory[J]. American Journal of Archaeology, 2009, 113(4):497-519 |

| [3] | Fan X, Harbottle G, Gao Q, et al. Brass before bronze? Early copper-alloy metallurgy in China[J]. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, 2012, 27(5):821-826 |

| [4] | Zinkina J, Christian D, Grinin L, et al. A Big History of Globalization: The Emergence of a Global World System[M]. Cham: Springer International Press, 2019, 25-49 |

| [5] | Miller NF, Spengler RN, Frachetti M. Millet cultivation across Eurasia: Origins, spread, and the influence of seasonal climate[J]. Holocene, 2016, 26(10):1566-1575 |

| [6] | Stevens CJ, Murphy C, Roberts R, et al. Between China and South Asia: A Middle Asian corridor of crop dispersal and agricultural innovation in the Bronze Age[J]. Holocene, 2016, 26(10):1541-1555 |

| [7] | Zhou X, Li X, Zhao K, et al. Early agricultural development and environmental effects in the Neolithic Longdong basin (eastern Gansu)[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2011, 56(8):762-771 |

| [8] | Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A. The origins of sedentism and farming communities in the Levant[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 1989, 3(4):447-498 |

| [9] | Brown TA, Jones MK, Powell W, et al. The complex origins of domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent[J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 2009, 24(2):103-109 |

| [10] | Lu H, Zhang J, Liu K-b, et al. Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(18):7367-7372 |

| [11] | Fuller DQ. Pathways to Asian Civilizations: Tracing the Origins and Spread of Rice and Rice Cultures[J]. Rice, 2011, 4(3):78-92 |

| [12] | Jiang L, Liu L. New evidence for the origins of sedentism and rice domestication in the Lower Yangzi River, China[J]. Antiquity, 2006, 80(308):355-361 |

| [13] | Zhao ZJ. The Middle Yangtze region in China is one place where rice was domesticated: phytolith evidence from the Diaotonghuan Cave, Northern Jiangxi[J]. Antiquity, 1998, 72(278):885-897 |

| [14] | 赵志军. 小麦传入中国的研究——植物考古资料[J]. 南方文物, 2015, 3:44-52 |

| [15] | Fuller DQ, Rowlands M. Towards a long-term macro-geography of cultural substances: food and sacrifice tradition in East, West and South Asia[J]. 见:王铭铭.中国人类学评论(第12辑)[C]. 北京: 世界图书出版公司, 2009, 12:1-37 |

| [16] | Glantz MH, Zonn IS. The Aral Sea: water, climate and environmental change in Central Asia[M]. Geneva: World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Press, 2005, 1-37 |

| [17] | Pomfret R. The economies of central Asia [M]. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014, 19-27 |

| [18] | Micklin P P. Desiccation of the Aral Sea: a water management disaster in the Soviet Union[J]. Science, 1988, 241(4870):1170-1176 |

| [19] | Smith D R. Environmental security and shared water resources in post-Soviet Central Asia[J]. Post-Soviet Geography, 1995, 36(6):351-370 |

| [20] | Micklin P. The Aral sea disaster[J]. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 2007, 35:47-72 |

| [21] | 王治来, 丁笃本. 中亚通史:近代卷[M]. 乌鲁木齐: 新疆人民出版社, 2004 |

| [22] | Adrianov B V, Mantellini S. Ancient Irrigation Systems of the Aral Sea Area: The History, Origin, and Development of Irrigated Agriculture [M]. Exeter: Oxbow Books Press, 2013, 95-134 |

| [23] | Dani A H, Masson V. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Vol. I The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 BC [M]. Paris: UNESCO Press, 1992, 441-458 |

| [24] | Dani AH, Staff U, Asimov M, et al. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Vol. II The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 BC to A[M]. Paris: UNESCO Press, 1994, 96-254 |

| [25] | Spengler R, Frachetti M, Doumani P, et al. Early agriculture and crop transmission among Bronze Age mobile pastoralists of Central Eurasia[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2014, 281(1783):20133382 |

| [26] | 袁政. 乌兹别克斯坦共和国苏尔汉河州简介[J]. 中亚信息, 2004, (1):30-32 |

| [27] | Пугаченкова Г А. Халчаян[M]. Ташкент: Наука УзССР, 1966. 1-287 |

| [28] | Brunet F. Pour une nouvelle étude de la culture néolithique de Kel’teminar, Ouzbékistan[J]. Paleorient, 2005, 87-105 |

| [29] | Hiebert FT. Origins of the Bronze Age oasis civilization in Central Asia[M]. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994, 109-129 |

| [30] | Hiebert FT. Production evidence for the origins of the Oxus Civilization[J]. Antiquity, 1994, 68(259):372-387 |

| [31] | Lamberg-Karlovsky C. The Oxus civilization: the Bronze Age of Central Asia[J]. Antiquity, 1994, 68(259):353-354 |

| [32] | Winckelmann S. Intercultural relations between Iran, the Murghabo-Bactrian Archaeological Complex (BMAC), Northwest India and Failaka in the Field of Seals[J]. East and West, 2000, 50(1-4):43-95 |

| [33] | 任萌. 塔吉克斯坦、乌兹别克斯坦考古调查——铜石并用时代至希腊化时代[J]. 文物, 2014, 7:54-67 |

| [34] | Masson VM. History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, AD 250 to 750[M]. Paris: UNESCO Press, 1996. 24-475 |

| [35] | 任萌. 塔吉克斯坦、乌兹别克斯坦考古调查——前贵霜时代至后贵霜时代[J]. 文物, 2015, 6:17-33 |

| [36] | 习通源. 塔吉克斯坦、乌兹别克斯坦考古调查——粟特时期[J]. 文物, 2019, 1:44-66 |

| [37] | Martínez FV, Gurt EJ, Hein A, et al. Tableware in the Hellenistic tradition from the city of Kampyr Tepe in ancient Bactria (Uzbekistan)[J]. Archaeometry, 2016, 58(5):736-764 |

| [38] | Пугаченкова Г А. Скульптура Халчаяна[M]. Москва: Искусство, 1971, 1-201 |

| [39] | Ramsey CB. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates[J]. Radiocarbon, 2009, 51(1):337-360 |

| [40] | Reimer PJ, Bard E, Bayliss A, et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0-50,000 years cal BP[J]. Radiocarbon, 2013, 55(4):1869-1887 |

| [41] | Kaniuth K. The metallurgy of the Late Bronze Age Sapalli culture (southern Uzbekistan) and its implications for the ‘tin question’[J]. Iranica antiqua, 2007, 42:23-40 |

| [42] | Miller NF. Agricultural development in western Central Asia in the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 1999, 8(1-2):13-19 |

| [43] | Brite EB, Marston JM. Environmental change, agricultural innovation, and the spread of cotton agriculture in the Old World[J]. Journal Of Anthropological Archaeology, 2013, 32(1):39-53 |

| [44] | Brite EB, Khozhaniyazov G, Marston JM, et al. Kara-tepe, Karakalpakstan: Agropastoralism in a Central Eurasian Oasis in the 4th/5th century AD Transition[J]. Journal Of Field Archaeology, 2017, 42(6):514-529 |

| [45] | Ranum P, Peña-Rosas JP, Garcia-Casal MN. Global maize production, utilization, and consumption[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2014, 1312(1):105-112 |

| [46] | 刘长江, 孔昭宸. 粟、黍籽粒的形态比较及其在考古鉴定中的意义[J]. 考古, 2004, 8:74-81 |

| [47] | 杨青, 李小强, 周新郢, 等. 炭化过程中粟、黍种子亚显微结构特征及其在植物考古中的应用[J]. 科学通报, 2011, 56(9):700-707 |

| [48] | Braadbaart F, van Bergen PF. Digital imaging analysis of size and shape of wheat and pea upon heating under anoxic conditions as a function of the temperature[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2005, 14(1):67-75 |

| [49] | Lee GA, Crawford GW, Liu L, et al. Archaeological soybean (Glycine max) in East Asia: does size matter?[J]. PLoS ONE, 2011, 6(11):e26720 |

| [50] | Chen F, Yu Z, Yang M, et al. Holocene moisture evolution in arid central Asia and its out-of-phase relationship with Asian monsoon history[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2008, 27(3-4):351-364 |

| [51] | Boomer I, Aladin N, Plotnikov I, et al. The palaeolimnology of the Aral Sea: a review[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2000, 19(13):1259-1278 |

| [52] | Rasmussen K, Ricketts R, Johnson T, et al. An 8,000 year multi-proxy record from Lake Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan[J]. Pages News, 2001, 9(2):5-6 |

| [53] | Ricketts RD, Johnson TC, Brown ET, et al. The Holocene paleolimnology of Lake Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan: Trace element and stable isotope composition of ostracodes[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2001, 176(1-4):207-227 |

| [54] | Ferronskii V, Polyakov V, Brezgunov V, et al. Variations in the hydrological regime of Kara-Bogaz-Gol Gulf, Lake Issyk-Kul, and the Aral Sea assessed based on data of bottom sediment studies[J]. Water Resources, 2003, 30(3):252-259 |

| [55] | Sorrel P, Popescu SM, Klotz S, et al. Climate variability in the Aral Sea basin (Central Asia) during the late Holocene based on vegetation changes[J]. Quaternary Research, 2007, 67(3):357-370 |

| [56] | Spengler RN, Chang C, Tourtellotte PA. Agricultural production in the Central Asian mountains: Tuzusai, Kazakhstan (410-150 BC)[J]. Journal Of Field Archaeology, 2013, 38(1):68-85 |

| [57] | Wu X, Miller NF, Crabtree P. Agro-pastoral strategies and food production on the Achaemenid frontier in Central Asia: a case study of Kyzyltepa in southern Uzbekistan[J]. Iran, 2015, 53(1):93-117 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |