内蒙古和林格尔土城子农业人群与林西井沟子游牧人群股骨中部的生物力学对比

收稿日期: 2020-09-10

修回日期: 2020-12-15

网络出版日期: 2022-04-13

基金资助

中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(XDB26000000);国家自然科学基金(41802020);中国博士后科学基金面上项目(2017M611449)

Biomechanical comparison of the middle femur between the Tuchengzi agricultural people and the Jinggouzi nomadic people from Inner Mongolia

Received date: 2020-09-10

Revised date: 2020-12-15

Online published: 2022-04-13

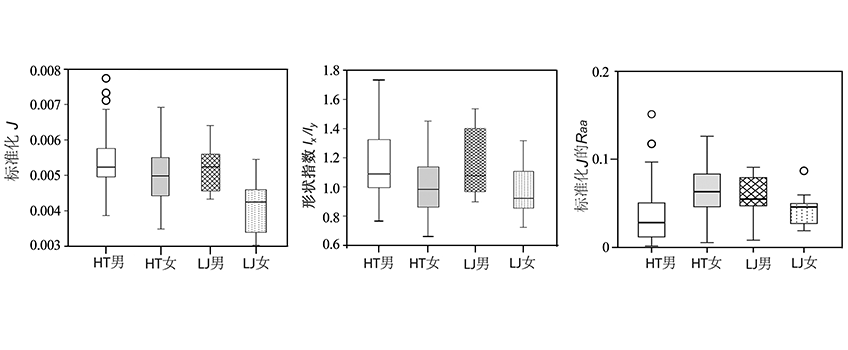

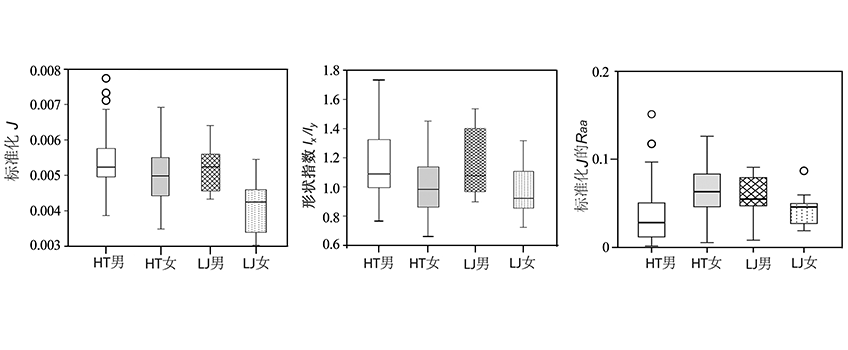

肢骨的形态结构可以反映人类进化、古代人群的生存适应性活动和生存环境等重要信息。基于“骨骼功能适应”和“杠杆原理”,有学者对不同生计方式的古代人群下肢股骨开展了大量的研究工作,但是,国内外尚未有关于农业人群和游牧人群股骨之间差异性研究的报道。本文选取两个具有代表性的古代人群,即内蒙古和林格尔土城子戍边农业人群和内蒙古林西井沟子游牧人群进行对比研究。通过对股骨骨干中部横断面生物力学分析发现,农业人群股骨粗壮度与游牧人群之间具有显著差异。前者的平均粗壮度较大,后者女性组下肢骨的活动强度明显较小,这可能与游牧人群经常从事骑马活动而下肢骨活动强度相对较少有关。农业人群股骨指数的变异范围均大于游牧人群,这可能与前者男性的士兵身份有关;同时,也提示土城子男性组股骨所反映的行为活动信息并不代表真正意义上的纯农业人群下肢骨行为模式,而是一种农业和士兵行为的混合模式。在性别分工上,井沟子组的男女性均从事骑马活动,两侧股骨受力较为一致,在两侧不对称性程度和骨干横断面形状上的男女差异不大;男性股骨的粗壮度要明显大于女性,这与井沟子组男性还从事一定的狩猎行为有关。与游牧人群女性较为纤细的股骨不同,土城子组女性作为典型的农业人群代表,其下肢骨整体的活动强度较大,几乎与同组的男性和井沟子组男性相当,组内的性别差异相对较小;骨干横断面形状的显著性差异说明,土城子组内部男性和女性的行为活动方式存在明显的性别分工。本文研究结果说明农业人群女性的下肢骨活动强度较大,在行为活动方式上,戍边农业人群具有更为明显的性别分工。

魏偏偏 , 张全超 . 内蒙古和林格尔土城子农业人群与林西井沟子游牧人群股骨中部的生物力学对比[J]. 人类学学报, 2022 , 41(02) : 238 -247 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2021.0014

The morphological structure of limb bones can reflect important information, i.e. human evolution, adaptive behavior of ancient populations and living environment, and vice versa. Most of these studies are based on “Bone Functional Adaptation” and “Beam Model”. Based on these, physical anthropologists have done a lot of research on femora of ancient populations with different lifestyle. However, there have been no related published studies about the femoral differences between agricultural and nomadic populations. Here, we provided detailed comparative assessment of femora from two archaeological sites, i.e. Tuchengzi and Jinggouzi from Inner Mongolia, with agricultural and nomadic lifestyle separately. Specifically, we analyzed diaphyseal structure of femoral three-dimensional visual digital model using methods of cross-sectional geometry. There was significant difference between Tuchengzi and Jinggouzi population. The mean level of femoral robusticity of Tuchengzi agricultural population was found to be larger than that of Jinggouzi nomadic population. The Jinggouzi female sample was significantly less robust than other groups, which should be correlated with the habitual riding behavior. The soldier status of Tuchengzi male sample may lead to the relatively larger variation range of femoral biomechanical index than that of Jinggouzi. It also indicated that the behavior information reflected by Tuchengzi male did not represent the typical agricultural population, but a mixture activity pattern. In terms of gender division of labor, the habitual riding behavior made the mechanical loading on bilateral femora relatively symmetry and similar cross-sectional shape of femoral midshaft, which led to little gender difference of femoral bilateral asymmetry in Jinggouzi sample. However, the males from nomadic population are involved in hunting behavior, which induces the significantly more robust femora that that of female. Compared to the slender femora of females in nomadic population, females in Tuchengzi sample, as the representative of the typical agricultural population, had almost the same robusticity as males of the same group, meaning that the agricultural females were more active in daily life. This also led to the relatively small gender difference of femoral robusticity within Tuchengzi sample. However, there is distinct difference of cross-sectional shape on femoral midshaft between Tuchengzi males and females, which suggesting that the activity pattern is significantly different between males and females of Tuchengzi sample.

Key words: Agricultural people; Nomadic people; Femoral diaphysis; Biomechanics

| [1] | Roux W. Der zuchtende Kampf der Teile, oder die ‘‘Teilauslee’’ im Organismus (Theorie der ‘‘funktionellen Anpassung’’)[M]. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann, 1881 |

| [2] | Wolff J. Das Gesetz der Transformation der Knochen[M]. Berlin: A. Hirchwild, 1892 |

| [3] | Wolff J. The law of bone remodeling[M]. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1986 |

| [4] | Roesler H. The history of some fundamental concepts in bone biomechanics. Journal of Biomechanics[J], 1987, 20:1025-1034 |

| [5] | Martin RB, Burr DB, Sharkey NA. Skeletal tissue mechanics[M]. New York: Springer, 1998 |

| [6] | Cowin SC. The false premis in Wolff ’s law[A]. In: SC Cowin (Ed.). Bone biomechanics handbook (2nd edition)[M]. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2001 |

| [7] | Ruff CB, Holt BH, Trinkaus E. Who’s afraid of the big bad Wolff? Wolff’s Law and bone functional adaptation[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2006, 129:484-498 |

| [8] | Lanyon E, Goodship AE, Pye CJ, et al. Mechanically adaptive bone remodeling[J]. Journal of Biomechanics, 1982, 15:141-154 |

| [9] | Carter DR. Mechanical loading histories and cortical bone remodeling[J]. Calcified Tissue International, 1984, 36:19-24 |

| [10] | Frost HM. Bone ‘‘mass’’ and the ‘‘mechanostat’’: a proposal[J]. Anatomical Record, 1987, 219:1-9 |

| [11] | Turner CH. Three rules for bone adaptation to mechanical stimuli[J]. Bone, 1998, 23:399-407 |

| [12] | Lieberman DE, Polk JD, Demes B. Predicting long bone loading from cross-sectional geometry[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2004, 123:156-171 |

| [13] | Pearson OM, Lieberman DE. The aging of Wolff’s ‘‘law:’’ ontogeny and responses to mechanical loading in cortical bone[J]. Year book Physical Anthropology, 2004, 47:63-99 |

| [14] | Ruff CB. Biomechanical analyses of archaeological human skeletons[A]. In: Katzenberg MA, Saunders SR (Eds.). Biological Anthropology of the Human Skeleton (2nd edition)[M]. Hoboken. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2008, 183-206 |

| [15] | Martin R, Saller K. Lehrbuch der Anthropologie in systematischer Darstellung. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. 1959 |

| [16] | Bräuer G. Anthropologie[A]. In: Knussman R (Ed.). Anthropologie[M]. Stuttgart: Fischer Verlag, 1988, 160-232 |

| [17] | Huiskes R. On the modelling of long bones in structural analyses[J]. Journal of Biomechanics, 1982, 15:65-69 |

| [18] | Lovejoy CO, Burstein AH, Heiple KG. The biomechanical analysis of bone strength: a method and its application to platycnemia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1976, 44:489-506 |

| [19] | Ruff CB, Hayes WC. Cross-sectional geometry of Pecos Pueblo femora and tibiae—a biomechanical investigation. I. Method and general patterns of variation[J]. American Physical Anthropology, 1983, 60:359-381 |

| [20] | Ruff CB. Biomechanics of the hip and birth in early Homo[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropological, 1995, 98:527-574 |

| [21] | Ruff CB. Long bone articular and diaphyseal structure in Old World monkeys and apes, I: locomotor effects[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2002, 119:305-342 |

| [22] | Ruff CB, Larsen CS, Hayes WC. Structural changes in the femur with the transition to agriculture on the Georgia coast[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1984, 64:125-136 |

| [23] | Stock JT, Pfeiffer SK. Long bone robusticity and subsistence behaviour among Later Stone Age foragers of the forest and fynbos biomes of South Africa[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2004, 31(7):999-1013 |

| [24] | 李法军. 鲤鱼墩遗址史前人类行为模式的骨骼生物力学分析[J]. 人类学学报, 36(2):193-215 |

| [25] | 何嘉宁. 军都山古代人群运动模式及生活方式的时序性变化[J]. 人类学学报, 35(2):238-245 |

| [26] | 张全超. 内蒙古和林格尔县新店子墓地人骨研究[D]. 长春:吉林大学, 2005 |

| [27] | 顾玉才. 内蒙古和林格尔县土城子遗址战国时期人骨研究[D]. 长春:吉林大学, 2007 |

| [28] | 魏偏偏. 周口店田园洞古人类股骨形态功能分析[D]. 北京:中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所, 2016, 93-96 |

| [29] | Macintosh AA, Davies TG, Ryan TM, et al. Periosteal versus true cross-sectional geometry: A comparison along humeral, femoral, and tibial diaphysis[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2013, 150:442-452 |

| [30] | Ruff CB, Scott WW, Liu AYC. Articular and diaphyseal remodeling of the proximal femur with changes in body mass in adults[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1991, 86:397-413 |

| [31] | Ruff CB, Holt BM, Niskanen M, et al. Stature and body mass estimation from skeletal remains in the European Holocene[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2012, 148:601-617 |

| [32] | McHenry HM. Body size and proportions in early Hominids[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1992, 87:407-431 |

| [33] | Grine FE, Jungers WL, Tobias PV, et al. Fossil Homo femur from Berg Aukas, northern Namibia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1995, 26:67-78 |

| [34] | Auerbach BM, Ruff CB. Limb bone bilateral asymmetry: variability and commonality among modern humans[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2006, 50:203-218 |

| [35] | Alexander G, Robling P, Felicia MH, et al. Improved Bone Structure and Strength After Long-Term Mechanical Loading is Greatest if Loading is Separated into Short Bouts[J]. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2002, 17(8):1545-1554 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |