古代病原微生物基因组的研究进展

收稿日期: 2022-03-24

修回日期: 2022-05-09

网络出版日期: 2022-08-10

基金资助

国家自然科学基金面上项目(42072018);中华文明探源研究项目(2020YFC1521607)

Progress in genomes of ancient pathogenic microorganisms

Received date: 2022-03-24

Revised date: 2022-05-09

Online published: 2022-08-10

古代病原微生物基因组研究对病理学、微生物学、考古学等领域均具有重要的价值。在过去的十年里,高通量测序和靶向富集技术的发展和应用使古代微生物基因组的获取成为可能,通过对古代人群样本中获取的宏基因组进行筛查,使得引发古代疫情的相关病原体的基因组得以重建,为研究人类传染病的起源、传播和演化提供了一个独特的窗口。在当今全球化的背景下,新发及再发传染性疾病的出现频率促使我们回顾过去,以便更好地了解现代病原菌出现和古代病原菌重新出现的过程和生态环境。在这篇文章中,我们总结了近十年古代病原微生物基因组水平的研究进展,并提出了这项研究所面临的挑战以及未来的研究前景和方向。

崔银秋 , 张昊 , 武喜艳 , 孙冰 , 周慧 . 古代病原微生物基因组的研究进展[J]. 人类学学报, 2022 , 41(04) : 764 -774 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2022.0025

Terrible epidemic disasters, such as the Black Death and smallpox, have run through the history of human society and have had a major impact on the development of human civilization and even the rise and fall of dynasties. Obtaining and analyzing the genomes of pathogens from major ancient outbreaks can not only reveal the causes of formation behind the devastating historical catastrophes of the era, but also be traced to the geographic spread and evolutionary patterns of pathogens, with important implications for the fields of pathology, microbiology, and archaeology.

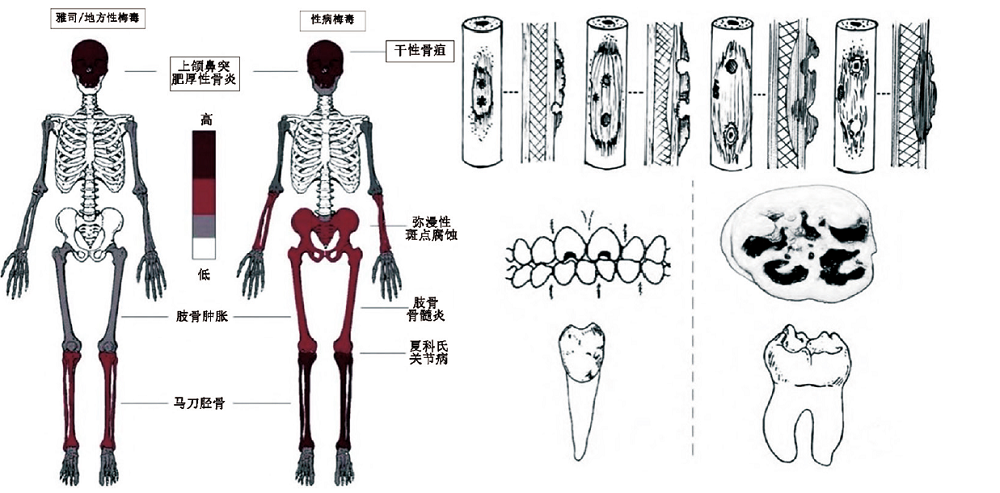

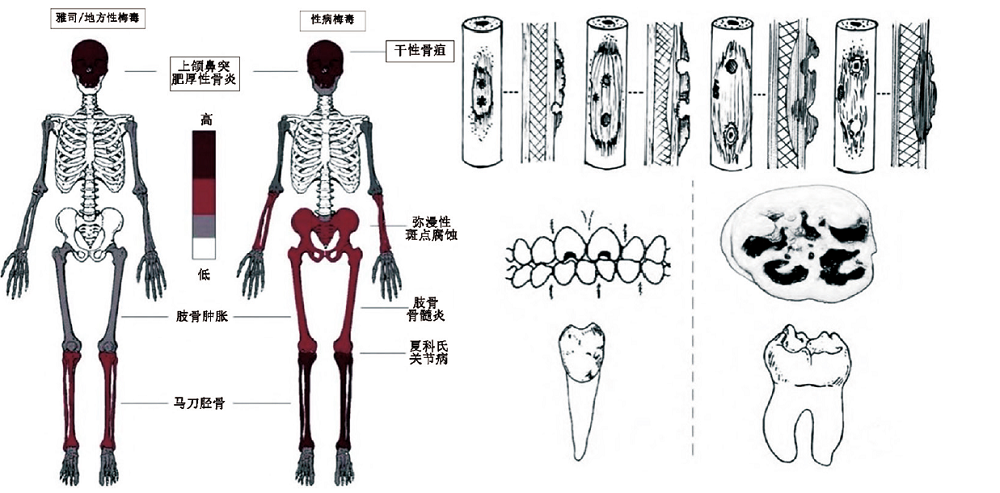

In this review, we first briefly introduce the plague disasters that occurred in history and their impact on human history, and then introduce traditional research methods on ancient plagues, including philology and paleopathology. We also point out the limitations of these traditional studies, such as differences in ancient and modern medical knowledge systems that make it difficult to draw firm conclusions from historical records, and morphological studies that are difficult to detect for those that do not cause overt skeletal damage.

In the past decade, the development and application of high-throughput sequencing have made it possible to recover ancient DNA, although we still need pay a lot attention to exogenous contamination, the ancient pathogen genome characterized by high degradation and low abundance can be retrieved by targeted enrichment technologies and powerful computational approach. Reconstructed pathogen genomes provide a unique window into the origin, spread, and evolution of human infectious diseases. In today’s globalized context, the frequency of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases prompts us to look back at past epidemics, which can help us better understand the processes and ecology of the emergence of modern pathogens and the re-emergence of ancient pathogens. we briefly describe the wet-lab procedures and analytical approaches used to study the microbial composition of ancient samples, and summarize studies Progress of ancient pathogen genomes using the study of ancient Yersinia pestis and Salmonella enterica genomes as examples, and exibit these studies have provide us the new insights to pathogen evolution, antibiotic resistance, and ancient health, cultural practices, and historical epidemics. Finally, we also propose the challenges facing this research and future research prospects and directions.

| [1] | 肯尼思·F·基普尔. 剑桥世界人类疾病史[M]. 译者:张大庆. 上海: 上海科技教育出版社, 2007: 907-918 |

| [2] | 西里尔·曼戈. 牛津拜占庭史[M]. 译者:陈志强,武鹏 北京: 北京师范大学出版社, 2015: 33-37 |

| [3] | 乔万尼·薄迦丘. 十日谈[M]. 译者:钱鸿嘉,泰和庠,田青. 南京: 译林出版社, 2011: 17-19 |

| [4] | [东汉]张仲景. 伤寒杂病论[M]. 北京: 中国中医药出版社, 2021: 1-4 |

| [5] | [南朝·宋范晔]. 后汉书[M]. 北京: 中华书局, 2012: 194-197 |

| [6] | Arrizabalaga J. The Black Death, 1346-1353: The Complete History[J]. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 2006, 80(1): 161-163 |

| [7] | Allison MJ, Mendoza D, Pezzia A. Documentation of a case of tuberculosis in pre-Columbian America[J]. The American review of respiratory disease, 1973, 107(6): 985-991 |

| [8] | 周亚威, 高国帅. 性病梅毒的古病理学研究回顾[J]. 人类学学报, 2022, 41(1): 157-168 |

| [9] | Bos KI, Schuenemann VJ, Golding GB, et al. A draft genome of Yersinia pestis from victims of the Black Death[J]. Nature, 2011, 478(7370): 506-510 |

| [10] | Fu QM, Meyer M, Gao X, et al. DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(6): 2223-2227 |

| [11] | Burbano HA, Hodges E, Green RE, et al. Targeted investigation of the Neandertal genome by array-based sequence capture[J]. Science, 2010, 328(5979): 723-725 |

| [12] | Bos KI, Kühnert D, Herbig A, et al. Paleomicrobiology: Diagnosis and Evolution of Ancient Pathogens[J]. Annu Rev Microbiol, 2019, 73: 639-666 |

| [13] | Devault AM, McLoughlin K, Jaing C, et al. Ancient pathogen DNA in archaeological samples detected with a Microbial Detection Array[J]. Scientific Reports, 2014, 4: 4245 |

| [14] | Sarkissian CD, Velsko IM, Fotakis AK, et al. Ancient Metagenomic Studies: Considerations for the Wider Scientific Community[J]. mSystems, 2021, 6(6): e01315-21 |

| [15] | Irving-Pease EK, Muktupavela R, Dannemann M, et al. Quantitative Human Paleogenetics: What can Ancient DNA Tell us About Complex Trait Evolution?[J]. Frontiers in Genetics, 2021, 12: 703541 |

| [16] | Duchêne S, Ho SYW, Carmichael AG, et al. The Recovery, Interpretation and Use of Ancient Pathogen Genomes[J]. Current Biology, 2020, 30(19): R1215-R1231 |

| [17] | 武喜艳. 新疆古代致病菌基因组学与进化历史研究[D]. 长春: 吉林大学, 2020: 1-13 |

| [18] | Tyler AJ, Pe'er I. An Introduction to Whole-Metagenome Shotgun Sequencing Studies[J]. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2021, 2243: 107-122 |

| [19] | Gaeta R. Ancient DNA and paleogenetics: risks and potentiality[J]. Pathologica, 2021, 113(2): 141-146 |

| [20] | 吴斯豪. 新疆塔里木盆地南缘铁器时代人群的基因组学研究[D]. 长春: 吉林大学, 2020: 13-18 |

| [21] | Firth C, Lipkin WI. The genomics of emerging pathogens[J]. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 2013, 14: 281-300 |

| [22] | Warinner C, Herbig A, Mann A, et al. A Robust Framework for Microbial Archaeology[J]. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 2017, 18: 321-356 |

| [23] | Kılınç GM, Kashuba N, Koptekin D, et al. Human population dynamics and Yersinia pestisin ancient northeast Asia[J]. Science Advances, 2021, 7(2): eabc4587 |

| [24] | Salo WL, Aufderheide AC, Buikstra J, et al. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in a pre-Columbian Peruvian mummy[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1994, 91(6): 2091-2094 |

| [25] | Monot M, Honoré N, Garnier T, et al. Comparative genomic and phylogeographic analysis of Mycobacterium leprae[J]. Nature Genetics, 2009, 41(12): 1282-1289 |

| [26] | Vradenburg JA. The role of treponematoses in the development of prehistoric cultures and the bioarchaeology of proto-urbanism of the central coast of Peru[M]. Columbia: University of Missouri-Columbia, 2001 |

| [27] | Immel A, Key FM, Szolek A, et al. Analysis of Genomic DNA from Medieval Plague Victims Suggests Long-Term Effect of Yersinia pestis on Human Immunity Genes[J]. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2021, 38(10): 4059-4076 |

| [28] | Spyrou MA, Bos KI, Herbig A, et al. Ancient pathogen genomics as an emerging tool for infectious disease research[J]. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2019, 20(6): 323-340 |

| [29] | Hansen HB, Damgaard PB, Margaryan A, et al. Comparing Ancient DNA Preservation in Petrous Bone and Tooth Cementum[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(1): e0170940 |

| [30] | Bos KI, Harkins KM, Herbig A, et al. Pre-Columbian mycobacterial genomes reveal seals as a source of New World human tuberculosis[J]. Nature, 2014, 514(7523): 494-497 |

| [31] | Schuenemann VJ, Singh P, Mendum TA, et al. Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae[J]. Science, 2013, 341(6142): 179-183 |

| [32] | Schuenemann VJ, Lankapalli AK, Barquera R, et al. Historic Treponema pallidum genomes from Colonial Mexico retrieved from archaeological remains[J]. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2018, 12(6): e0006447 |

| [33] | Vågene ÅJ, Herbig A, Campana MG, et al. Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico[J]. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2018, 2(3): 520-528 |

| [34] | Marciniak S, Prowse TL, Herring DA, et al. Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 1st-2nd century CE southern Italy[J]. Current Biology, 2016, 26(23): R1220-R1222 |

| [35] | Maixner F, Kyora BK, Turaev D, et al. The 5300-year-old Helicobacter pylori genome of the Iceman[J]. Science, 2016, 351(6269): 162-165 |

| [36] | Duggan AT, Perdomo MF, Piombino-Mascali D, et al. 17th Century Variola Virus Reveals the Recent History of Smallpox[J]. Current Biology, 2016, 26(24): 3407-3412 |

| [37] | Biagini P, Thèves C, Balaresque P, et al. Variola virus in a 300-year-old Siberian mummy[J]. N Engl J Med, 2012, 367(21): 2057-2059 |

| [38] | Carpenter ML, Buenrostro JD, Valdiosera C, et al. Pulling out the 1%: whole-genome capture for the targeted enrichment of ancient DNA sequencing libraries[J]. American Journal Of Human Genetics, 2013, 93(5): 852-864 |

| [39] | Key FM, Posth C, Krause J, et al. Mining Metagenomic Data Sets for Ancient DNA: Recommended Protocols for Authentication[J]. Trends in genetics, 2017, 33(8): 508-520 |

| [40] | Harbeck M, Seifert L, Hänsch S, et al. Yersinia pestis DNA from skeletal remains from the 6(th) century AD reveals insights into Justinianic Plague[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2013, 9(5): e1003349 |

| [41] | Giffin K, Lankapalli AK, Sabin S, et al. A treponemal genome from an historic plague victim supports a recent emergence of yaws and its presence in 15th century Europe[J]. Scientific reports, 2020, 10(1): 9499 |

| [42] | Rasmussen S, Allentoft ME, Nielsen K, et al. Early divergent strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 years ago[J]. Cell, 2015, 163(3): 571-582 |

| [43] | Valtueña AA, Mittnik A, Key FM, et al. The Stone Age Plague and Its Persistence in Eurasia[J]. Current Biology, 2017, 27(23): 3683-3691 |

| [44] | Luhmann N, Doer D, Chauve C. Comparative scaffolding and gap filling of ancient bacterial genomes applied to two ancient Yersinia pestisgenomes[J]. Microbial Genomics, 2017, 3(9): e000123 |

| [45] | Song YJ, Wang J, Yang RF, et al. Historical variations in mutation rate in an epidemic pathogen, Yersinia pestis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2013, 110(2): 577-582 |

| [46] | Wagner DM, Keim PS, Scholz HC, et al. Yersinia pestis and the three plague pandemics--authors' reply[J]. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2014, 14(10): 919 |

| [47] | Damgaard PdB, Marchi N, Rasmussen S, et al. 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes[J]. Nature, 2018, 557(7705): 369-374 |

| [48] | Kirk MD, Pires SM, Black RE, et al. World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial, Protozoal, and Viral Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis[J]. PLoS Medicine, 2015, 12(12): e1001921 |

| [49] | Zhou ZM, Lundstrøm I, Tran-Dien A, et al. Pan-genome Analysis of Ancient and Modern Salmonella enterica Demonstrates Genomic Stability of the Invasive Para C Lineage for Millennia[J]. Current Biology, 2018, 28(15): 2420-2428 |

| [50] | Key FM, Posth C, Esquivel-Gomez LR, et al. Emergence of human-adapted Salmonella enterica is linked to the Neolithization process[J]. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2020, 4(3): 324-333 |

| [51] | Wu XY, Ning C, Key FM, et al. A 3,000-year-old basal S. enterica lineage from Bronze Age Xinjiang suggests spread along the Proto-Silk Road[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2021, 17(9): e1009886 |

| [52] | Spyrou MA, Keller M, Tukhbatova RI, et al. Phylogeography of the second plague pandemic revealed through analysis of historical Yersinia pestis genomes[J]. Nature Communications, 2019, 10(1): 4470 |

| [53] | Susat J, Lübke H, Immel A, et al. A 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer already plagued by Yersinia pestis[J]. Cell Reports, 2021, 35(13): 109278 |

| [54] | Stephens JC, Reich DE, Goldstein DB, et al. Dating the origin of the CCR5-Delta32 AIDS-resistance allele by the coalescence of haplotypes[J]. American Journal of human genetics, 1998, 62(6): 1507-1515 |

| [55] | Sabeti PC, Walsh E, Schaffner SF, et al. The case for selection at CCR5-Delta32[J]. PLoS Biology, 2005, 3(11): e378 |

| [56] | Lindo J, Huerta-Sanchez E, Nakagome S, et al. Demographic and immune-based selection shifts before and after European contact inferred from 50 ancient and modern exomes from the Northwest Coast of North America[J]. BioRxiv 051078 |

| [57] | Kyora BK, Nutsua M, Boehme L, et al. Ancient DNA study reveals HLA susceptibility locus for leprosy in medieval Europeans[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 1569 |

| [58] | Guellil M, Keller M, Dittmar JM, et al. An invasive Haemophilus influenzae serotype b infection in an Anglo-Saxon plague victim[J]. Genome Biology, 2022, 23(1): 22 |

| [59] | Spyrou MA, Tukhbatova RI, Feldman M, et al. Historical Y. pestis Genomes Reveal the European Black Death as the Source of Ancient and Modern Plague Pandemics[J]. Cell Host & Microbe, 2016, 19(6): 874-881 |

| [60] | Gansauge MT, Meyer M. Selective enrichment of damaged DNA molecules for ancient genome sequencing[J]. Genome research, 2014, 24(9): 1543-1549 |

| [61] | Ginolhac A, Rasmussen M, Gilbert MT, et al. mapDamage: testing for damage patterns in ancient DNA sequences[J]. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27(15): 2153-2155 |

| [62] | Hübler R, Felix MK, Warinner C, et al. HOPS: automated detection and authentication of pathogen DNA in archaeological remains[J]. Genome biology, 2019, 20(1): 280 |

| [63] | Kumar S, Stecher G, Peterson D, et al. MEGA-CC: computing core of molecular evolutionary genetics analysis program for automated and iterative data analysis[J]. Bioinformatics, 2012, 28(20): 2685-2686 |

| [64] | Warinner C, Speller C, Collins MJ. A new era in palaeomicrobiology: prospects for ancient dental calculus as a long-term record of the human oral microbiome[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2015, 370(1660): 20130376 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |