泥河湾盆地板井子遗址2015年出土石制品的剥片技术

收稿日期: 2023-10-17

修回日期: 2024-01-08

网络出版日期: 2024-10-10

基金资助

国家社会科学基金青年项目(2021CKG002);国家重点研发计划项目(2020YFC1521500)

Core reduction technology of stone artifacts unearthed in 2015 from the Banjingzi site in Nihewan Basin

Received date: 2023-10-17

Revised date: 2024-01-08

Online published: 2024-10-10

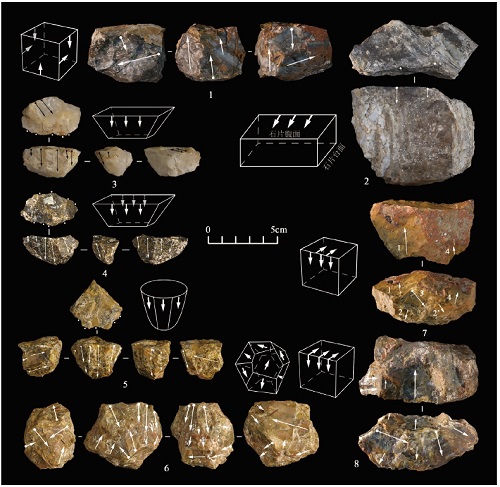

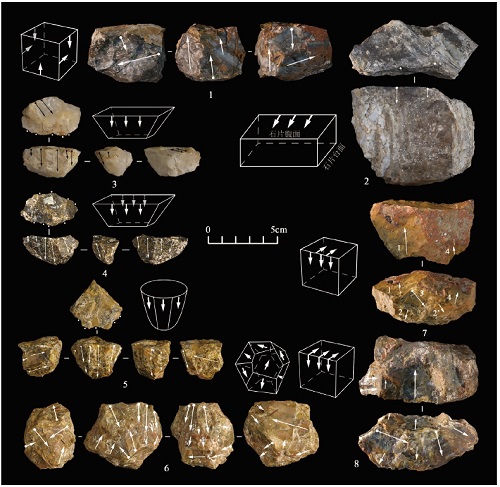

板井子是泥河湾盆地及中国北方晚更新世早期的重要遗址,目前光释光年代在距今9~8万年。本文重点分析了板井子遗址2015年出土石制品的剥片技术及相关的人类行为。遗址第4、5、6层出土石制品分别为61件、2563件、31件。石料皆以燧石为主,石英岩、白云岩等其他原料很少。主文化层即第5层石核毛坯以岩块、断块为主,皆硬锤直接打击。石核类型多样,包括试打片石核、简单石核、局部两面石核、盘状石核四类。多选择平整的面为台面,有零星修理台面的现象,剥片面无预制修整,利用剥片面棱脊的情况明显。普通石核倾向于对同一剥片面采用单向连续开发,台面与剥片面转换无明显的规律性与组织性。盘状石核有一定比例,是一种较独立的剥片方法,但并不十分典型规范。完整石片多为宽薄型,以长度在20~40 mm的居多。第4、6层标本零星,剥片情况与第5层基本一致。该遗址的石核剥片整体上属于中国北方石核-石片技术体系,与早、中更新世等泥河湾盆地更早时段遗址的剥片技术相比,表现出连续发展的特征。

任进成 , 李锋 , 陈福友 , 高星 . 泥河湾盆地板井子遗址2015年出土石制品的剥片技术[J]. 人类学学报, 2024 , 43(05) : 712 -726 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2024.0079

Banjingzi site, located in the eastern margin of the Nihewan Basin, is considered one of the most significant occurrences that formed during the early Late Pleistocene in North China. Since its discovery in 1984, several excavations have been conducted at this site. In 2015, a new excavation project was organized by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IVPP), in collaboration with the Institute of Hebei Provincial Cultural Relics. This project uncovered an area of 36 m2, resulting in the discovery of 4417 specimens. These specimens include stone artifacts, animal bones (excluding sieved pieces), and natural pebbles (L≥50 mm) from layers 4, 5, and 6. Analysis of site formation processes indicates that layer 5 was formed in the near primary context, while the other two layers were transported by waterflow from nearby areas. The archaeological materials were predominantly buried around 90-80 ka BP, as determined by the latest work on layer 5 using the OSL method. This paper presents a study on core reduction strategies of stone artifacts from three cultural layers uncovered in 2015. The findings of this study will enhance our understanding of lithic technology and the associated human behaviors that occurred during the early Late Pleistocene in North China.

The excavation in 2015 yielded a total of 2655 lithics. Out of these, 61 were found in layer 4, 2563 in layer 5, and 31 in layer 6. The stone artifacts were made using different raw materials sourced from local ancient rock outcrops and gravel layers. Chert was the most common material found in the lithic assemblage, while others, such as quartzite, dolomite, were used less frequently. In layer 5, the lithic assemblage comprises 111 cores, 419 flakes, 786 chunks, 1076 debris, 162 retouched tools and 9 hammerstones. Cores were primarily knapped on rocks, chunks, pebbles and flakes using direct percussion with hard hammers. Four categories have been identified: test cores (n=23), casual cores (n=68), partial bifacial cores (n=5), and discoid cores (n=15). Most cores were chipped casually and did not show any special technological organization. They were mainly exploited through unidirectional flaking on the same knapping surface. Discoid cores, which were assigned to the bifacial centripetal recurrent method, are considered to be an independent and relatively stable technological system at Banjingzi site. There are no obvious traces indicating intentional preparation of the debitage surfaces of cores, although a few striking platforms were occasionally retouched. Techno-complexes found in layer 4 and layer 6 shared the same characteristics as layer 5, but only a few lithics, including 3 casual cores with unifacial flaking method, were unearthed. Overall, the core reduction strategies at Banjingzi exhibit the main attributes of core-flake industries commonly found in North China.

Key words: Nihewan Basin; Banjingzi site; early Late Pleistocene; Core-flake industry

| [1] | Yang SX, Deng CL, Zhu RX, et al. The Paleolithic in the Nihewan Basin, China: Evolutionary history of an Early to Late Pleistocene record in Eastern Asia[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 2020, 29(3): 125-142 |

| [2] | 赵海龙, 谭培阳, 孙雪峰, 等. 河北泥河湾盆地油房北旧石器地点的发现与研究[J]. 第四纪研究, 2021, 41(1): 164-177 |

| [3] | 任进成, 李锋, 王晓敏, 等. 河北阳原县板井子旧石器时代遗址2015年发掘简报[J]. 考古, 2018, 11: 3-14+2 |

| [4] | 任进成, 王法岗, 李锋, 等. 泥河湾盆地板井子旧石器时代遗址的形成过程[J]. 人类学学报, 2021, 40(3): 378-392 |

| [5] | 卫奇. 石制品观察格式探讨[A].见:邓涛,王原(主编).第八届古脊椎动物学术年会文集[C]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 2001, 209-218 |

| [6] | Casini. The meaning of ‘Kombewa’ method in middle Palaeolithic: techno-economic analysis of lithicassemblages from Riparo Tagliente (VR), Carapia (RA), Podere Camponi (BO) and Fossato Conca d’Oro (MT)[J]. Museologia Scientifica e Naturalistica, 2010, 6: 123-130 |

| [7] | Toth N. The artefact assemblage in the light of experimental studies. In: Isaac GL. (Ed.). Koobi Fora Research Project, vol. 5: Plio-Pleistocene Archaeology[M]. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997, 363-388 |

| [8] | de la Torre I, Mora R, Dominguez-Rodrigo M, et al. The Oldowan industry of Peninj and its bearing on the reconstruction of the technological skills of Lower Pleistocene hominids[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 2003, 44(2): 203-224 |

| [9] | Brumm A, Moore MW, van den Bergh GD, et al. Stone technology at the Middle Pleistocene site of Mata Menge, Flores, Indonesia[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2010, 37(3): 451-473 |

| [10] | Yang SX, Petraglia MD, Hou YM, et al. The lithic assemblage of Donggutuo, Nihewan basin: Knapping skills of Early Pleistocene hominins in North China[J]. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(9): e0185101 |

| [11] | 侯亚梅, 刘扬, 李英华, 等. 泥河湾盆地三棵树旧石器遗址2008年试掘报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2010, 29(3): 227-241 |

| [12] | 贾兰坡, 卫奇. 阳高许家窑旧石器时代文化遗址[J]. 考古学报, 1976, 2: 97-114+207-212 |

| [13] | 贾兰坡, 卫奇, 李超荣. 许家窑旧石器时代文化遗址1976年发掘报告[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类学, 1979, 4: 277-293+347-350 |

| [14] | 王法岗. 侯家窑遗址综合研究[D]. 硕士研究生毕业论文, 石家庄: 河北师范大学, 2012 |

| [15] | 谢飞, 李珺, 刘连强. 泥河湾旧石器文化[J]. 石家庄:花山文艺出版社, 2006 |

| [16] | Bo?da E. Le débitage discoie et le débitage levallois récurrent centripète[J]. Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Fran-?aise, 1993, 90(6): 392-404 |

| [17] | Li H, Li ZY, Gao X, et al. Technological behavior of the early Late Pleistocene archaic humans at Lijing (Xuchang, China)[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2019, 11: 3477-3490 |

| [18] | Yang SX, Hou YM, Yue JP, et al. The lithic assemblages of Xiaochangliang, Nihewan basin: Implications for Early Pleistocene hominin behaviour in North China[J]. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(5): e0155793 |

| [19] | Pei SW, Xie F, Deng CL, et al. Early Pleistocene archaeological occurrences at the Feiliang site, and the archaeology of human origins in the Nihewan Basin, North China[J]. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(11): e0187251 |

| [20] | 裴树文, 贾真秀, 马东东, 等. 泥河湾盆地麻地沟E5旧石器地点的遗址成因与石器技术[J]. 人类学学报, 2016, 35(4): 493-508 |

| [21] | Yang SX, Wang FG, Xie F, et al. Technological innovations at the onset of the Mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition in high-latitude East Asia[J]. National Science Review, 2021, 8(1): nwaa053 |

| [22] | 曹明明. 泥河湾盆地后沟遗址初步研究[D]. 硕士研究生毕业论文, 北京: 中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所, 2007 |

| [23] | 马宁, 裴树文, 高星. 许家窑遗址74093地点1977年出土石制品研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2011, 30(3): 275-288 |

| [24] | Ma DD, Pei SW, Xie F, et al. Earliest prepared core technology in Eurasia from Nihewan (China): Implications for early human abilities and dispersals in East Asia[J]. PNAS, 2024, 121(11): e2313123121 |

| [25] | 刘连强, 王法岗, 杨石霞, 等. 泥河湾盆地马梁遗址第10地点2016年出土石制品研究[J]. 人类学学报, 2018, 37(3): 419-427 |

| [26] | 裴树文, 马东东, 贾真秀, 等. 蔚县盆地吉家庄旧石器遗址发掘报告[J]. 人类学学报, 2018, 37(4): 510-528 |

| [27] | Wu XJ, Crevecoeur I, Liu W, et al. Temporal labyrinths of eastern Eurasian Pleistocene humans[J]. PNAS, 2014, 111(29): 10509-10513 |

| [28] | Li ZY, Wu XJ, Zhou LP, et al. Late Pleistocene archaic human crania from Xuchang, China[J]. Science, 2017, 355(6328): 969-972 |

| [29] | Liu W, Wu XZ, Pei SW, et al. Huanglong Cave: A Late Pleistocene human fossil site in Hubei Province, China[J]. Quaternary International, 2010, 211(1-2): 29-41 |

| [30] | Liu W, Jin CZ, Zhang YQ, et al. Human remains from Zhirendong, South China, and modern human emergency in East China[J]. PNAS, 2010, 107(45): 19201-19206 |

| [31] | Liu W, Martinón-Torres M, Cai YJ, et al. The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China[J]. Nature, 2015, 526(7575): 696-699 |

| [32] | Chen FH, Welker F, Shen CC, et al. A late Middle Pleistocene Denisovan mandible from the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Nature, 2019, 569: 409-412 |

| [33] | 栗静舒, 张双权, 高星, 等. 许家窑遗址马科动物的死亡年龄[J]. 人类学学报, 2017, 36(1): 62-73 |

| [34] | 张双权, 李占扬, 张乐, 等. 河南灵井许昌人遗址大型食草类动物死亡年龄分析及东亚现代人行为的早期出现[J]. 科学通报, 2009, 54(19): 2857-2863 |

| [35] | Doyon L, Li ZY, Wang H, et al. A 115000-year-old expedient bone technology at Lijing, Henan, China[J]. PLoS ONE, 2021, 16(5): e0250156 |

| [36] | 张改课, 王社江, 鹿化煜, 等. 陕西南郑疥疙洞旧石器洞穴遗址发掘获重要成果[N]. 中国文物报,2019-12-6-08 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |