Ritualistic cranial surgery in the Qijia Culture (2300-1500 BC), Gansu, China

Received date: 2017-12-14

Revised date: 2018-09-18

Online published: 2020-09-10

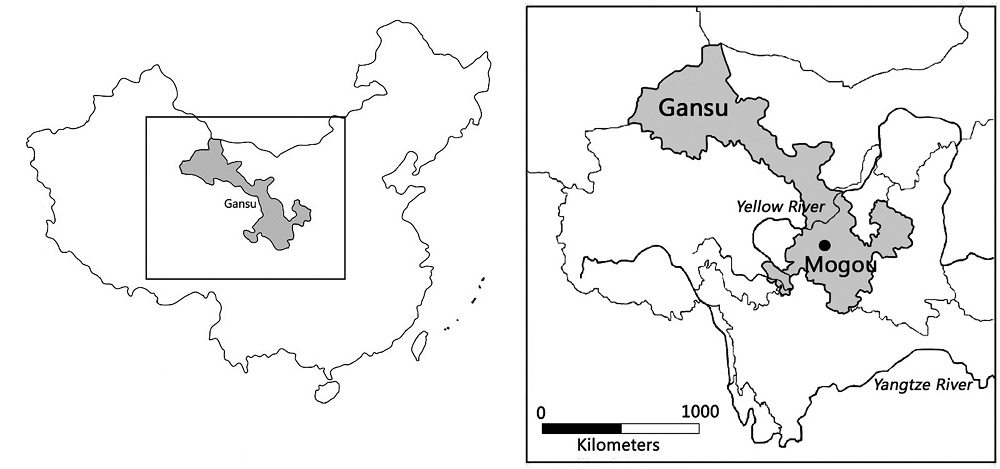

Evidence of cranial surgery, in the form of trepanations, has been found at prehistoric archaeological sites from all over the world. Within this large body of evidence, it is clear that trepanations vary in size, location and the reason for which they were performed. Numerous trepanations have been discovered at archaeological sites across China, but very few have come from Qijia Culture (2300-1500 BC) sites in Northwest China. This research describes a well-healed trepanation on an adult male individual(M179:R2) from the Mogou site and compares it to contemporaneous examples from China that date from 3000~0 BC in order to elucidate how and why this procedure was performed. A small circular opening with slightly irregular, but well-healed, margins was identified on the left parietal bone, immediately posterior to the coronal suture. The characteristics of the lesion suggest that the scraping method was employed to create the opening. Unfortunately, the advanced stage of healing made the identification of the specific instrument used in the trepanation impossible. The characteristics of the incision and the archaeological context led the authors to propose that the trepanation on M179:R2 was performed as part of a magico-ritual, rather than for a non-ritual medical purpose. This is supported by the presence of multiple individuals, mainly men, from the Mogou site with similar well-healed trepanations.

Key words: Trepanation; Surgery; Northwest China; Mogou; Bronze Age

M DITTMAR Jenna , Xiaoya ZHAN , BERGER Elizabeth , Ruilin MAO , Hui WANG , Yongsheng ZHAO , Huiyuan YE . Ritualistic cranial surgery in the Qijia Culture (2300-1500 BC), Gansu, China[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2019 , 38(03) : 389 -397 . DOI: 10.16359/j.cnki.cn11-1963/q.2019.0035

| [1] | Han KX, Chen XC. The archaeological evidence of trepanation in early China[J]. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 2007,27:22-27 |

| [2] | Roberts CA, Mckinley J. Review of trepanations in British antiquity focusing on funerary context to explain their occurrence[A]. In: Arnott R, Finger S, Smith CUM, eds. Trepanation: History, Discovery, Theory. Swets and Zeitlinger Publishers: Lisse, 2003: 55-78 |

| [3] | Zhang Q, Wang Q, Kong BY, et al. A scientific analysis of cranial trepanation from an Early Iron Age cemetery on the ancient Silk Road in Xinjiang, China. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2018,10(6):1319-1327 |

| [4] | Weber J, Wahl J. Neurosurgical aspects of trepanations from Neolithic times. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2006,16:536-545. DOI: 10.1002/oa.844 |

| [5] | Arnott R, Finger S, Smith CUM. Trepanation: History, discovery, theory. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger Publishers, 2007 |

| [6] | He XL. Skull opening before death or perforation after death: Discussion on Chinese skull opening 5000 years back. Journal of Guanxi University for Nationalities, 2010,32(1):58-70 |

| [7] | Han KX, Tan JZ, He CK. Trepanation in Ancient China. Fudan: University Press, 2007 |

| [8] | Lisowski FP. Prehistoric and early historic trepanation. In: Brothwell D, Sandison AT, eds. Diseases in Antiquity. Springfield: Charles C Thomas, 1967, 651-672 |

| [9] | Grattan JHG, Singer CJ eds. Anglo-Saxon magic and medicine: Illustrated specially from the semi-pagan Text “Lacnunga” (No.3). London: Oxford University Press, 1952 |

| [10] | Lv XL, Li ZG, Li YX. Prehistoric skull trepanation in China. World Neurosurgery, 2013,80(6):897-899 |

| [11] | Liu XY, Lightfoot E, O’Connell TC, et al. From necessity to choice: Dietary revolutions in west China in the second millennium BC. World Archaeology, 2014, 46(5):661-680 DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2014.953706 |

| [12] | Mao R, Qian YP, Xie Y, et al. Gansu Lintan Mogou Qijia wenhua mudi fajue jianbao[Excavation of Mogou cemetery of Qijia culture in Gansu Province]. Wenwu(Cultral Relics), 2009,641:10-24 |

| [13] | Xie Y, Qian YP, Mao RL, et al. 2009. Gansu Lintan xian Mogou Qijia wenhua mudi: A Qijia cultural cemetery, Mogou in Lintan County, Gansu Province. Kaogu(Archaeology), 2009,49(7):10-17 |

| [14] | Chen HH. The Qijia Culture of the Upper Yellow River Valley. In: Underhill AP ed. A companion to Chinese archaeology. Chichester: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013, 105-124 |

| [15] | Liu L, Chen XC. The archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012 |

| [16] | Womack A, Jaffe Y, Zhou J, et al. Mapping Qijiaping: New work on the type-site of the Qijia Culture(2300-1500 BC) in Gansu Province, China. Journal of Field Archaeology, 42(6): 488-502 DOI: 10.1080/00934690.2017.1384669 |

| [17] | Buikstra JE, Mielke JH. Demography, diet and health. US: Academic Press, 1985 |

| [18] | Phenice TW. A newly developed visual method of sexing the os pubis. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1969,30:297-301 |

| [19] | Klales AR, Ousley SD, Vollner JM. A revised method of sexing the human innominate using Phenice’s nonmetric traits and statistical methods. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2012,149(1):104-114 |

| [20] | Lovejoy C, Meindl RS, Pryzbeck TR, et al. Chronological metamorphosis of the auricular surface of the illium: A new method for the determination of age at death. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1985,68:15-28 |

| [21] | Brooks S, Suchey JM. Skeletal age determination based on the os pubis: A comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks methods. Human Evolution, 1990,5(3):227-238 |

| [22] | Buckberry JL, Chamberlain AT. Age estimation from the auricular surface of the ilium: A revised method. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2002, 119(3):231-239 DOI: 10.1002/ajpa.10130 |

| [23] | Verano JW. Differential diagnosis: Trepanation. International Journal of Paleopathology, 2016,14, 1-9 |

| [24] | Nerlich AG, Peschel O, Zink A, et al. The pathology of trepanation: Differential diagnosis, healing and dry bone appearance in modern cases. In: Arnott R, Finger S, Smith CUM eds. Trepanation: History, discovery, theory. Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger Publishers, 2003, 43-54 |

| [25] | Parker SJ, Scragg D. Skulls, symbols and surgery: A review of evidence for trepanation in Anglo-Saxon England and a consideration of the motives behind the practice. In: Scragg DG ed. Superstition and popular medicine in Anglo-Saxon England, Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies, Manchester: University of Manchester, 1989, 73-84 |

| [26] | Zhao YS. Gansu Lintan Mogou mudi rengu yanjiu(A research on the human skeletons of Mogou graveyard, Lintan County, Gansu Province). Jilin University, Department of Archaeology and Museology. Changchun, China. PhD, 2014 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |