Traumas of human bones from the Yulongwan site in Kaifeng, Henan

Received date: 2023-03-16

Accepted date: 2023-06-16

Online published: 2023-12-14

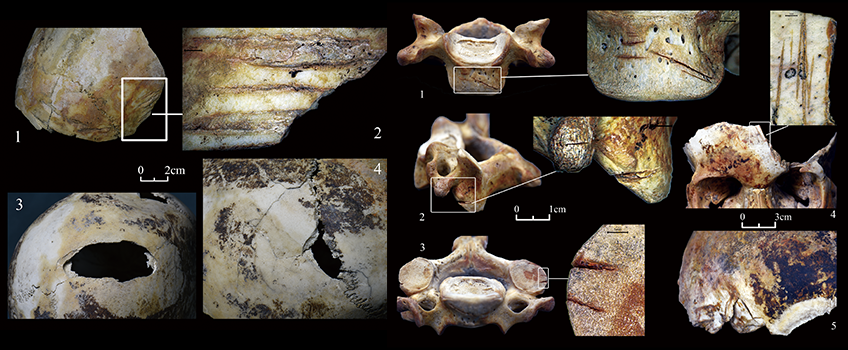

In this paper, human bone remains excavated from the Yulongwanan site, an architectural site of Ming Dynasty, in the southeast Kaifeng City were identified, and the human bone specimens (R2, R3, R5, R6, R11 and R12) with premortem traumas were used as research materials to distinguish the marks of chopping, smashing, cutting and burning on human bones. The marks were measured with a vernier caliper, including maximum length, width and depth. Three traits of type, location and quantity for describing the morphology of the marks were recorded. According to the macroscopic and microscopic criteria of indirect heat exposure at low temperature, the surface morphology of human bones in containers was observed and analyzed respectively by naked eye and scanning electron microscope (SEM). The results showed that: 1) R6 (female, 40~45 years old) in an supine extended position, which was shallowly buried in the Ming culture layer, only had multiple chopmarks on the skull, but the postcranial bones were complete, so it is unclear why the skull was chopped; 2) R3 (gender unknown, about 9 years old) lied on its right side with flexed limbs in the silted clay layer; the postcranial bones were complete, so two smashmarks on R3’s skull could have been caused by bricks’ or beams’ hitting when the house collapsed; 3) The human bones in containers (R2, R5, R12) and house (R11) showed signs of violent hacking and mutilation. The micromorphometric analysis of cutting and chopping marks on human bones suggests that these marks occured in slaughtering of fresh bodies. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images also indicated that R2 and R5 presented the diffusion and degradation of collagen fibrils, smooth and compact surfaces, and closed bone pores. The low temperature burning of R12 made collagen degrade, formed gelatinous mass, and made the pores indistinguishable. Those bones (R2, R5, R12) were significantly different from R11, which had the hierarchical structure, typical of cortical bone morphology. Therefore the human bones in containers were supposed to be heated at a low temperature. The bones of R2, R5, R11 and R12 shared a number of characteristics that had come to be recognized as baseline criteria for identifying cannibalism in the archaeological record: Lack of formal burial, under-representation of bones, extensive perimortem lesions, and burning. These bones can be used as the evidence of cannibalism, which corroborate the human tragedy recorded in historical data from the perspective of bioarchaeology. The human bones unearthed from the Yulongwan Ming Dynasty architecture site may be the most credible evidence of cannibalism, which provide anthropological data for understanding deeply the cannibalism of ancient human and the social history of the Ming Dynasty.

Key words: Ming Dynasty; Human bones; Trauma; Cannibalism

Lei SUN , Junwei WAN , Jing TANG , Ting REN . Traumas of human bones from the Yulongwan site in Kaifeng, Henan[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2023 , 42(06) : 779 -792 . DOI: 10.16359/j.1000-3193/AAS.2023.0063

| [1] | 吴朋飞. 崇祯河决开封城的灾害环境复原[J]. 苏州大学学报(哲学社会科学版), 2021(2): 185-192 |

| [2] | 刘益安. 汴围湿襟录校注[M]. 郑州: 中州书画社, 1982, 3-66 |

| [3] | [清]谷应泰. 明史纪事本末[M]. 北京: 中华书局,卷七十八, 1977 |

| [4] | 河南省文物考古研究院, 开封市文物考古研究所. 开封御龙湾小区明代建筑遗址的发掘[J]. 华夏考古, 2019(2): 53-80 |

| [5] | 邵象清. 人体测量手册[M]. 上海: 上海辞书出版社, 1985, 34-56 |

| [6] | 朱泓. 体质人类学[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2004, 92-106 |

| [7] | 陈世贤. 法医人类学[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 1998, 83-86 |

| [8] | Buikstra JE, Ubelaker D. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains[M]. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 44. 1994, 15-47 |

| [9] | Scheuer L, Black S. The Juvenile Skeleton[M]. Elsevier Academic Press, 2004, 1-406 |

| [10] | Sylwia ?ukasik. Victims of a 17th century massacre in Central Europe: Perimortem trauma of castle defenders[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 2019, 29: 281-293 |

| [11] | Williamson M, Johnston C, Symes S, et al. Interpersonal violence between 18th century native Americans and Europeans in Ohio[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2003, 122: 113-122 |

| [12] | Lewis JE. Identifying sword marks on bone: Criteria for distinguishing between cut marks made by different classes of bladed weapons[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(7): 2001-2008 |

| [13] | Andrushko VA, Latham K, Grady DL, et al. Bioarchaeological evidence for trophy-taking in prehistoric central California[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2005, 127: 375-384 |

| [14] | 祁国琴. 动物考古学所要研究和解决的问题[J]. 人类学学报, 1983, 2(3): 293-300 |

| [15] | Bosch P, Alemán I, Moreno C, et al. Boiled versus un-boiled, a study on neolithic and contemporary human bones[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38: 2561-2570 |

| [16] | Solari AS, Olivera D, Gordillo I, et al. Cooked bones? Method and practice for identifying bones treated at low temperature[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2015, 25(4): 426-440 |

| [17] | Lovell NC. Trauma analysis in paleopathology[J]. Yearbook of physical anthropology, 1997, 40: 139-170 |

| [18] | Kremer C, Racette S, Dionne CA, et al. Discrimination of falls and blows in blunt head trauma: Systematic study of the hat brim line rule in relation to skull fractures[J]. Journal of Forensicences, 2008, 53(3): 716-719 |

| [19] | Waldron T. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology: Palaeopathology[M]. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009, 165 |

| [20] | Bush H, Stirland A. Romano-British decapitation burials: a comparison of osteological evidence and burial ritual from two cemeteries[J]. Anthropologie, 1991, 29: 205-210 |

| [21] | 王娟, 侯彦峰. 荥阳鲁庄墓地2016年度发掘西晋、宋金墓葬出土动物遗存鉴定报告[A]. 见:河南省文物考古研究院,荥阳市文物保护中心(编).荥阳鲁庄墓地[R]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2021, 333-335 |

| [22] | 侯彦峰, 王娟. 信阳城阳城址八号墓鼎实用牲研究[J]. 华夏考古, 2020(4): 79-88 |

| [23] | Eileen M, Ilia G, Yuri C, et al. Prehistoric old world scalping: new cases from the cemetery of Aymyrlyg, south Siberia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2002, 106(1): 1-10 |

| [24] | Mednikova MB. Scalping in Eurasia[J]. Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia, 2002, 41(4): 57-67 |

| [25] | Wolf D, Bueschgen D, Troy C. Evidence of prehistoric dcalping at Vosberg, Central Arizona[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 1996(6): 230-248 |

| [26] | Ca′ceres I, Lozano M, Saladie P. Evidence for Bronze Age Cannibalism in El Mirador Cave (Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain)[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2007, 133: 899-917 |

| [27] | Santana J, Rodríguez-Santos FJ, Camalich-Massieu MD, et al. Aggressive or funerary cannibalism? Skull-cup and human bone manipulation in Cueva de El Toro (Early Neolithic, southern Iberia)[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2019, 169: 31-54 |

| [28] | Boulestin B, Zeeb-Lanz A, Jeunesse C, et al. Mass cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture at Herxheim (Palatinate, Germany)[J]. Antiquity, 2009, 83: 968-982 |

| [29] | White TD. Prehistoric Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346[M]. Princeton University Press, 1992, 3-163 |

| [30] | Turner II CG, Morris NT. A massacre at Hopi[J]. American Antiquity, 1970, 35(3): 320-331 |

| [31] | Lambert P, Billman B, Leonard B. Explaining variability in mutilated human bone assemblages from the American Southwest: A case study from the southern Piedmont of Sleeping Ute Mountain, Colorado[J]. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 2000(10): 49-64 |

| [32] | 卜风贤. 灾民生活史:基于中西社会的初步考察[J]. 古今农业, 2010(4): 42-50 |

| [33] | 郭俊然. 秦汉时期的食人现象述论[J]. 乌鲁木齐职业大学学报, 2013, 22(3): 45-48 |

| [34] | 胡鹏. 五代时期的食人原因及方法探微[J]. 安康学院学报, 2017, 29(4): 78-82 |

| [35] | 朱钤. 考古发现中的“人吃人”现象[J]. 大自然探索, 2004(5): 74-76 |

| [36] | 贾兰坡. 远古的食人之风[J]. 化石, 1979(1): 12-13 |

| [37] | 孙其刚. 考古所见缺头习俗的民族学考查[J]. 中国国家博物馆馆刊, 1998(2): 84-96 |

| [38] | 梁志远. 亳县“特殊案件”的记述[J]. 炎黄春秋, 2014(7): 39-43 |

| [39] | Villa P. Cannibalism in Prehistoric Europe[J]. Evolutionary Anthropology, 1992, 93-104 |

| [40] | De eur A, White TD, Valensi P, et al. Neanderthal cannibalism at Moula-Guercy, Arde`che, France[J]. Science, 1999, 286: 128-131 |

| [41] | Degusta D. Fijian cannibalism: Osteological evidence from Navatu[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1999, 110: 215-241 |

| [42] | Marlar RA, Leonard BL, Billman BR, et al. Biochemical evidence of cannibalism at a prehistoric Puebloan site in southwestern Colorado[J]. Nature, 2000, 407: 74-78 |

| [43] | 张钊贻. 《狂人日记》中的“吃人”与中国文化及“国民性”:兼论“吃人”是否中国风俗[J]. 海南师范大学学报(社会科学版). 2021, 34(1): 2-10 |

| [44] | 韦亮节, 蒙元耀. 壮族《董永和仙女歌》“食人”叙事阐释[J]. 民族文学研究, 2021, 39(4): 69-77 |

| [45] | 王文婷. 玛莉探秘食人部落[J]. 自然与科技, 2014(3): 42-47 |

| [46] | 蒂姆·怀特. 人类也存在食人历史[J]. 科学大观园, 2017, 24: 53-55 |

| [47] | 刘静. 基于古籍库中典型描述语检索的人口大量死亡事件时空特征与原因分析[D]. 西安: 陕西师范大学, 2018: 73-90 |

| [48] | 殷淑燕, 刘静. 明崇祯年间“人相食”事件时空特征、原因与影响研究[J]. 干旱区资源与环境, 2019, 33(8): 70-77 |

| [49] | 陈岭. 明清时期灾荒食人现象的时空分布分析[J]. 宜春学院学报, 2012, 34(6): 62-66 |

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |